Key Findings

- There is a geographic mismatch between the location of individuals who use digital platforms and the location where those products are developed. In 2020, while 40 percent of the value created in information industries originated in North America, 40 percent of global internet users were based in East and Southeast Asia.

- The growth of the digital economy in recent decades has been paired with policy debates about the taxes digital companies pay and where they pay them.

- In the absence of a multilateral change to taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities.

policies, a significant number of countries adopted unilateral tax measures targeted at digital businesses, including digital services taxes (DSTs), gross-based withholdingWithholding is the income an employer takes out of an employee’s paycheck and remits to the federal, state, and/or local government. It is calculated based on the amount of income earned, the taxpayer’s filing status, the number of allowances claimed, and any additional amount of the employee requests.

taxes, and digital permanent establishment rules. - Currently, 18 countries have implemented unilateral DSTs, and Canada will be joining this group soon.

- The United States, home of most of the companies impacted by DSTs, plans to eliminate DSTs either though a multilateral agreement or through trade threats and potential trade wars.

- The multilateral solution of Amount A from Pillar One creates clear winners and losers, and the United States holds the keys to getting the treaty ratified or not. Nevertheless, even if the treaty gets ratified, it may not result in the removal of all DSTs.

- If a multilateral solution is not reached, DSTs will continue to spread, resulting in uncertainty and double taxationDouble taxation is when taxes are paid twice on the same dollar of income, regardless of whether that’s corporate or individual income.

. - One hundred and one countries have implemented a value-added tax (VAT) or goods and services tax (GST) on cross-border online sales. In the EU, VAT revenues collected from these measures increased sevenfold in seven years, between 2015 and 2022. Additionally, the maximum revenue potential of a VAT on e-commerce is 2.5 times higher than that of tariffs at the current rates.

- Instead of utilizing these distortionary taxes, countries should expand consumption taxes to include digital services and products, achieving a neutral broadening of the tax baseThe tax base is the total amount of income, property, assets, consumption, transactions, or other economic activity subject to taxation by a tax authority. A narrow tax base is non-neutral and inefficient. A broad tax base reduces tax administration costs and allows more revenue to be raised at lower rates.

.

Key Recommendations

The digital tax debate is far from over, and policymakers should follow sound principles in developing, refining, and (in some cases) removing digital tax policies.

In two policy areas, consumption and corporate income taxes (and associated permanent establishment rules), countries are working to extend their existing rules to digital businesses. This presents an opportunity to move toward the equal treatment of physical and digital business models, but also real challenges to align standards and implement policies on a multilateral basis. Policies in these areas should meet a high bar for alignment with other jurisdictions, minimize complexity and compliance costs, and avoid differential treatment of targeted business sectors.

In two other policy areas, digital services taxes and gross-based withholding taxes, countries are relying on novel, but distortive and discriminatory, approaches to taxing digital businesses. These policies have the potential to lead to an economically harmful tax and trade war and should be avoided.

The following recommendations should be used to guide the design and implementation of policies addressing the challenges of taxing digital business models.

Consumption Taxes

The expansion of consumption taxes to include digital services and products can achieve a neutral broadening of the tax base. Because the purpose of consumption taxes is to tax where consumption occurs, broadening tax bases to digital consumption is simply an extension of that principle. However, differences in compliance costs, rates, or registration thresholds can create new distortions or unnecessarily increase compliance costs.

Countries should pursue:

- A broad consumption taxA consumption tax is typically levied on the purchase of goods or services and is paid directly or indirectly by the consumer in the form of retail sales taxes, excise taxes, tariffs, value-added taxes (VAT), or an income tax where all savings is tax-deductible.

base that includes digital services and products to achieve equal treatment between digital and physical businesses - Alignment with general standards for collecting data on remote sales and digital transactions

- Compliance requirements designed to minimize costs associated with building new systems and identifying the location of a sale or customer

Countries should avoid:

- Policies targeting digital cross-border transactions with rates that differ from those that would apply to similar, local commerce

Digital Services Taxes

Digital services taxes should, by and large, be removed to avoid the distortions that taxes on revenues create. Absent repeal, countries should clarify ways that businesses can avoid being taxed twice on digital income.

Countries should pursue:

- Clear timelines for removal of digital services taxes to avoid a harmful tax and trade war

- Policies that clearly allow for relief from double taxation (for instance, when both a DST and normal corporate income taxA corporate income tax (CIT) is levied by federal and state governments on business profits. Many companies are not subject to the CIT because they are taxed as pass-through businesses, with income reportable under the individual income tax.

may apply to the same earnings in the same country)

Countries should avoid:

- Adopting digital services taxes to prevent the distortions that such revenue-based taxes create

Digital Permanent Establishment Rules

When developing policies to tax corporate income of digital businesses, some countries are adjusting their definitions of permanent establishments. However, this immediately creates the potential for double taxation.

While disagreements among countries on the allocation of taxable corporate income remain, the challenges associated with some countries attempting to tax digital business income without creating double taxation will continue. Though comprehensive reforms to international taxation would also address the digitalization of the economy, countries will likely remain focused on reforms targeted at digital business models rather than taking up the challenge to broadly adopt fundamental reforms.[1]

Outside of a fundamental reform to the international tax system, countries should recognize that navigating definitions of digital permanent establishments comes with risks.

Countries should pursue:

- Multilateral negotiations when developing new approaches for taxing the corporate income of nonresident businesses

Countries should avoid:

- Rules targeted at specific industries or sectors that would create unstable policies in the context of a rapidly changing and digitalizing economy

- Unilateral pursuit of digital permanent establishment regulations that are likely to result in double taxation and harm efforts to coordinate policies

Gross-Based Withholding Taxes on Digital Services

Gross-based withholding taxes on digital services are a poor proxy for corporate income taxes and represent a shortcut to taxing digital companies without considering the challenges of identifying a virtual permanent establishment. Policymakers should avoid relying on gross-based withholding taxes to tax digital businesses that do not have a local presence.

Countries should avoid:

- Relying on policies that are neither efficient nor transparent as rough substitutes for either consumption or income taxes

Introduction

The digitalization of the economy has been a key focus of tax debates in recent years. Political debates have focused on the differences between taxing physical business operations and virtual operations. These debates have intersected with multiple layers of tax policy, including consumption and corporate tax policies. Novel policies have also been developed, including equalization levies and digital services taxes alongside the more common use of gross-based withholding taxes targeted at digital services.

However, in some cases, political expediency has outpaced consistent policy designs in line with sound principles of tax policy. As policymakers continue to evaluate the options to tax digital businesses, they should avoid creating new distortive tax policies driven by political agendas.

This paper reviews a multitude of digital tax policies around the world with a focus on Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries and points out the various flaws and benefits associated with the wide set of proposals.

What Are Digital Taxes?

The digital economy means many different things. The same is true for digital taxes. In this paper, digital taxes include policies that specifically target businesses that provide products or services through digital means using a special tax rate or tax base.[2]

These include policies that extend existing rules to ensure a neutral tax policy toward all businesses, such as when a country extends its value-added tax to include digital services. They also include special corporate tax rules designed to identify when a digital company has a permanent establishment even without a physical presence.

This paper reviews and analyzes digital taxes using the following categories:

- Consumption taxes

Consumption taxes are value-added taxes and other taxes on the sale of final goods or services. Countries have been expanding their consumption taxes to include digital goods and services.

- Digital services taxes

Digital services taxes are gross revenue taxes with a tax base that includes revenues derived from a specific set of digital goods or services or based on the number of digital users within a country.

- Gross-based withholding taxes on digital services

Gross-based withholding taxes are used by some countries instead of corporate taxes or consumption taxes to tax revenue of digital firms connected to transactions within a jurisdiction. As gross incomeFor individuals, gross income is the total pre-tax earnings from wages, tips, investments, interest, and other forms of income and is also referred to as “gross pay.” For businesses, gross income is total revenue minus cost of goods sold and is also known as “gross profit” or “gross margin.”

taxes, these policies do not substitute for income or consumption taxation.

- Digital permanent establishment rules

These policies redefine permanent establishments to include digital companies that have no physical presence in a jurisdiction. These virtual or digital permanent establishments are usually defined using specific criteria, such as engagement with the local market.

Principles for Digital Taxation

Just as with other areas of tax policy, it is important to evaluate digital taxes using principles of sound tax policy: simplicity, transparency, neutrality, and stability.[3] Many digital tax policies fail to adhere to these principles by design.

Simplicity

Tax codes should be easy for taxpayers to comply with and for governments to administer and enforce. Digital tax policies fail the simplicity test when they leave important definitions unclear or add unnecessary compliance challenges for businesses that are trying to understand how much tax they owe. This arises in unclear standards for identifying in-scope business elements for virtual permanent establishments and digital services taxes. Though the broad designs of some digital taxes are conceptually simple, the complexity arises in the practical details of identifying relevant users and revenues, sometimes without clear guidance on how to do so. Governments also face challenges evaluating whether a digital company has paid the correct amount of tax, especially for digital tax policies that rely on the location of users.

Transparency

Tax policies should clearly and plainly define what taxpayers must pay and when they must pay it. Disguising tax burdens in complex structures should be avoided. Digital taxes are sometimes designed as thinly veiled proxies for other taxes (either consumption or corporate taxes) rather than pure extensions of those existing policies. Additionally, digital services taxes and gross-based withholding taxes usually have low statutory rates, but because they apply to revenues rather than income the tax burden is effectively much higher than the rate implies.

Neutrality

The purpose of taxes is to raise needed revenue, not to favor or punish specific industries, activities, and products. Some digital taxes work to create neutrality between digital business models and other businesses. Extending consumption taxes to include digital products and services can result in the neutral treatment of consumption. Expanding permanent establishment rules to create equivalent virtual permanent establishments in line with clear market connections can also improve neutrality. However, targeted digital services taxes create unequal tax treatment based on a business’s industry or sector.

Stability

Taxpayers deserve consistency and predictability in the tax code. Governments should avoid enacting temporary tax laws, including tax holidays, amnesties, and retroactive changes. Many digital tax policies are designed to be temporary, with some timelines tied to international agreements on changes. Temporary tax policy creates uncertainty and challenges for both administration and compliance. Additionally, digital taxes often target specific business activities that are constantly evolving as the digitalization of the economy continues. Policies should not rely on definitions of business activities that are subject to change in a dynamic economy.

The Digital Tax Debate

The growth of the digital economy in recent decades has been paired with policy debates about the taxes that digital companies pay and where they pay them. Many digital business models do not require a physical presence in countries where they have sales, reaching customers through remote sales and service platforms.

Business models like social media companies, e-commerce marketplaces, cloud services, and web-based services platforms have all motivated targeted tax policies. In some cases, the policies are extensions of old rules to new players, while other policies are special taxes directed specifically at a business or platform.[4]

Consumption tax policies have shifted to account for the growth of products and services delivered through digital means, often without a business having a taxable presence in the country where the products are consumed. Additionally, policymakers have examined ways to change corporate taxes to capture the activity of digital firms in countries.

In response to the difference in tax burdens, policymakers have sought new taxation tools targeted (in some cases) at the same businesses that are eligible for the targeted preferences.[5]

Because the major digital companies are multinational businesses, the digital tax discussion has led to different tax proposals at the OECD, the United Nations (UN), and the European Union (EU) since without a multilateral agreement, individual country policies are likely to intersect or contradict one another, resulting in double taxation.[6]

Digital Value Creation

Changing international rules on digital taxation will impact both where and how much tax the impacted digital businesses pay. International norms of corporate income taxation rely on the concept of value creation to decide where a business pays taxes. In the digital tax debate, a new angle to the value creation debate has arisen.

Proponents of digital taxation often argue that digital value creation should account for the value contributed by users of social media platforms or e-commerce websites because the data provided by user habits are then translated into targeted advertisements or other customized services.[7]

Attributing value to a user that accesses a free service is economically challenging because there is no price signal connected to the single user, and creating a network of users as a value-creating asset comes with similar measurement and valuation challenges. Although network effects are prevalent in some digital business models, such effects are also common throughout other parts of the economy and do not give rise to special tax rules.[8]

Policies that follow the logic of value created by users imply that the location of value creation for tax purposes would necessarily change. Just as the global population is not evenly distributed across countries, recent measures of value created by digital companies are concentrated in certain jurisdictions.

In 2020, a bit more than 40 percent of global internet users were in East and Southeast Asia, while 22 percent of value created in information industries originated there. Conversely, just 12 percent of internet users in 2020 resided in North America while 40 percent of value created in information industries originated there.

Multilateralism or Unilateralism?

Because of the mismatch in the current distribution of internet users and the location of digital production, changing tax rules to reflect where users are located would change where businesses owe and pay taxes. This highlights the political challenge of rewriting the rules in ways that impact which countries receive tax revenue from digital businesses. This is where the OECD has stepped in to manage negotiations among more than 140 countries.[9]

The conflicting policies that have arisen unilaterally—such as digital services taxes—require multilateral action to avoid harmful tax and trade wars.[10] However, the solutions on the table at the OECD already violate the principles of sound tax policy. As the work on Pillar One[11] continues, this paper takes stock of existing digital tax measures and highlights the strengths and weaknesses of the various approaches.

Consumption Taxes and the Digital Economy

Consumption tax changes to account for digital services and goods sold over the internet are often meant to level the playing field between international and domestic providers. Consumption tax policies can remove the bias in favor of the digital acquisition of goods and services relative to their local, physical acquisition. When broadening the VAT base to include digital goods and services, equal treatment in tax rates and compliance costs needs to be ensured.

The increasing digitalization of the economy has changed the nature of retail distribution. Many digital companies engage in remote sales in countries where they don’t have a physical presence. Consumption-based taxation of remote sales or services allows for taxing a transaction when a seller or service provider has no local physical presence.

The estimated e-commerce sales value, which includes business-to-business (B2B) and business-to-consumer (B2C) sales, reached $26.7 trillion globally in 2019, the equivalent of 30 percent of the global gross domestic product (GDP).[12]

The value of global B2C e-commerce in 2019 was $4.9 trillion, representing 18 percent of all e-commerce. Of this, cross-border B2C e-commerce sales amounted to $440 billion in 2019, representing an increase of 9 percent over 2018.

The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) estimates that 1.48 billion people, or one-quarter of the world’s population aged 15 and older, made purchases online in 2019.[13] The interest in buying from foreign suppliers continued to expand. The share of cross-border online shoppers to all online shoppers rose from 17 percent ($200 million) in 2016 to 25 percent ($360 million) in 2019.

As cross-border e-commerce increases, governments want to charge tax based on the location of the purchaser of the product or service. Value-added tax (VAT) and goods and services tax (GST) rules are being amended to ensure that foreign suppliers—which typically do not have a local physical presence—become liable for the collection and remittance of these taxes. Not having a physical presence in the country poses a great challenge to the seller as it needs to deal with disparate and changing requirements in each of the countries where it has sales. This presents unique bookkeeping requirements, as well as having to deal with paperwork or online forms in the language of that country. This can be both a time-consuming and resource-intensive process for businesses.

WTO Moratorium

Additionally, since 1998, members of the World Trade Organization (WTO) have agreed not to impose customs duties on electronic transmissions. The moratorium of customs on digital trade, worth an estimated $1.3 billion,[14] was due to expire in March 2024 but was extended, for now, until March 2026.[15] E-commerce could be at risk if countries decide not to renew the moratorium and instead opt to place tariffs on e-commerce alongside consumption and digital taxation measures.

This will impose a great risk not only on the digital economy but also on economies more broadly. The OECD found that the relative fiscal benefits of lifting the moratorium would be small and vastly outweighed by the disruption to gains in consumer welfare and export competitiveness.[16] While tariffs could collect, on average, between 0.01 percent and 0.33 percent of the overall government revenue, the net effect of imposing customs duties and mutual tariffTariffs are taxes imposed by one country on goods or services imported from another country. Tariffs are trade barriers that raise prices and reduce available quantities of goods and services for U.S. businesses and consumers.

increases by trading partners negatively impacts investment, employment, growth, and tax revenue.[17]

Remote Sales

For VAT purposes, goods are referred to as “tangible property.” The VAT treatment of supplies of goods depends on the location of the goods at the time of the transaction or as a result of the transaction. When a transaction involves goods being moved from one jurisdiction to another, the exported goods are generally free of VAT in the seller’s jurisdiction, while the imports are subject to domestic VAT in the buyer’s jurisdiction.

Remote Services

When services are considered, the VAT legislation in many countries tends to define a “service” as “anything that is not otherwise defined,” or a “supply of services” as anything other than a “supply of goods.” While this generally also includes intangibles, some jurisdictions regard intangibles as a separate category. To identify the place of taxation of service for VAT purposes, a wide range of proxies can be used, including the place of performance of the service, the location of the supplier, the location of the customer, or the location of the tangible property related to the service. The OECD’s International VAT/GST Guidelines recommend that the place of taxation is the location of the customer, especially for B2B supplies of services.[18] In this way, it avoids the need for cross-border refunds of VAT to businesses that have acquired services abroad.

What OECD Countries Are Doing

Most of the countries in the OECD have implemented consumption taxes on a broad number of digital products and services. Yet, some countries have excluded certain types of products or services like e-books, live broadcasts, online courses, etc., or decided to apply a lower tax rate for certain categories.

In general, B2B transactions apply a “reverse charge” mechanism, where the recipient, not the seller, deals with the tax. The problem arises when transactions are B2C. Many countries require sellers with no physical presence in the buyer’s country to register for VAT purposes if their annual sales in the country exceed a certain threshold. The threshold ranges from $4,552[19] in Norway to $109,905 in Switzerland, while countries like Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Mexico, South Korea, Turkey, or the United Kingdom have no minimum threshold.[20]

Also, to determine customer location, some countries require businesses to collect information on billing address, IP address of the device used in the transaction, bank details, or country code of phone number. Finally, once registered, businesses are expected to file VAT returns. In Mexico, providers are expected to report monthly on VAT collected.

Revenue Impact

Currently, 101 countries have implemented a VAT or GST on cross-border online sales.[21] More than 50 countries worldwide have already implemented OECD recommendations for the effective collection of a VAT. Following OECD guidance on tax collection,[22] the European Union VAT revenues collected from these measures increased sevenfold, from €3 billion ($3.2 billion) in 2015 and €4.5 billion ($4.8 billion) in 2018 to over €20 billion ($21.35 billion) in 2022.[23]

Nevertheless, the European Union’s total VAT revenue in 2015 was €853 billion ($911 billion), and €1.2 trillion ($1.3 trillion) in 2022.[24] Therefore, VAT revenue raised from these measures increased from 0.5 percent to 1.6 percent of the total VAT raised in the EU.

Additionally, as a recent report shows, the maximum revenue potential of a VAT on e-commerce is 2.5 times higher than that of tariffs at the current rates. Yet, for five countries among the lower-middle and low-income economies, the potential revenue from tariffs would exceed VAT revenue by more than 0.1 percentage points of total revenue. However, by improving the VAT C-efficiency (how close a country’s VAT system is to an ideal VAT) that is relatively low in low- and lower-middle-income countries, VAT revenue would also surpass potential tariff revenues in these countries.[25]

The Downside of Introducing Consumption Taxes on Cross-Border Transactions

More than 175 countries have already implemented requirements for companies to use e-invoicing for reporting taxes on business transactions.[26] International companies face serious challenges to comply with disparate and changing requirements in each of the countries where they have sales. Even if only the software requirements were to be taken into consideration and the continuous updates needed, the operating costs rise significantly with each country where they have sales.

Complying with the reporting requirements can be incredibly expensive, and potentially prohibitive.

Reporting systems may become an obstacle for smaller or newer firms to enter the market or operate across borders. This is bad both for competition and for consumers. Also, if there is a threshold for compliance, companies will try to shift their activities to avoid reaching that threshold.

Additionally, enforcing local rules on companies established abroad is difficult, especially if there is no cooperative agreement between the countries involved. The supplier might not register in the country of destination if its sales exceed the threshold to avoid additional compliance obligations, and the country of origin for the supplier has no incentives to ensure that the selling regime is applied correctly. Many tax authorities lack resources to deal with the volume of transactions to be verified. Also, depending on the level of tax, the VAT treatment of certain digital goods could significantly increase prices for certain services.

Countries should consider doing an in-depth cost-benefit analysis before implementing consumption-based taxation of remote sales. As seen in one of the previous sections, the VAT collected from cross-border transactions continues to increase as a percent of the country’s total VAT revenue. As e-commerce continues to grow, so will VAT revenue from cross-border digital transactions. This will broaden the VAT tax base and could allow for lower rates in the long term to raise similar amounts of revenue.

Best Practices

First, the neutrality of the tax system is important. Taxes should not interfere in taxpayers’ decisions, making them prefer one form of trade over another: for example, cross-border electronic commerce over local conventional commerce. Therefore, countries that apply the same VAT rate for cross-border transactions and domestic ones, and for both digital and non-digital products, offer a neutral tax system. Also, based on the same neutrality principle, similar VAT exemption/registration thresholds should apply to foreign and domestic sellers. A neutral VAT expansion to digital services removes the distortion of digital consumption being untaxed while similar goods or services acquired locally face tax.

Second, it’s important to implement systems that are efficient and easy to deal with from an administrative and compliance standpoint. According to the Ottawa Taxation Framework Conditions,[27] a tax system should be efficient in the sense that “compliance costs for taxpayers and administrative costs for the tax authorities should be minimized as far as possible.” Nevertheless, the amount of information that businesses have to collect in some countries regarding the transactions and their customers are burdensome and, in some cases, could violate privacy laws governing trade secrets.[28] In Italy, for example, businesses must now issue electronic receipts to all customers. Additionally, companies need to register for a “digital address” number with the tax authority and obtain the digital addresses of all their customers and suppliers.[29] Policymakers need to balance the compliance costs of information requirements against the need to verify compliance with VAT rules.

Digital Services Taxes

As outlined previously, there has been growing concern about the existing international tax system not properly capturing the digitalization of the economy. Under current international tax rules, multinationals generally pay corporate income tax where production occurs rather than where consumers or, specifically for the digital sector, users are located. However, some argue that through the digital economy, businesses (implicitly) derive income from users abroad but, without a physical presence, are not subject to corporate income tax in that foreign country.

To address those concerns about a misalignment between value creation and corporate taxation, the OECD has been hosting negotiations with over 140 countries that aim to adapt the international tax system. As explained in detail in the section below on corporate taxation and the digital economy, the Pillar One proposal would realign international taxing rights with new measures of value creation, requiring multinational businesses to pay some of their corporate income taxes where their consumers or users are located.

However, despite these ongoing multilateral negotiations, several countries have decided to unilaterally move ahead with a different form of digital taxation—namely, digital services taxes—as a proxy for corporate taxation. Instead of adapting the international tax rules to better capture the digital economy, countries impose DSTs to tax large businesses based on their revenues derived from certain digital services provided to domestic users or consumers.

Digital Services Taxes around the World

Over the last six years, jurisdictions around the world have announced, proposed, and implemented DSTs. First proposed as an EU-wide tax, DSTs are now unilateral measures found on every continent.

EU Proposal for a DST

In March 2018, the European Commission put forth a proposal to establish rules that allow for corporate taxation of businesses with a significant digital presence.[30] While this is the long-term objective of the proposal, it also proposes a DST that would be implemented as an interim measure until the significant digital presence rules are in place.[31]

The EU’s DST would be a 3 percent tax on revenues from digital advertising, online marketplaces, and sales of user data generated in the EU. Businesses are in scope if their annual global revenues exceed €750 million ($801 million[32]) and EU revenues exceed €50 million ($54 million). The tax was estimated to generate €5 billion ($5.34 billion) annually for EU Member States,[33] translating to 0.08 percent of total tax revenues collected in the EU in 2018.[34]

The European Commission was unable to find the necessary unanimous support for the proposal to be adopted. However, it has indicated that, in case the OECD does not reach an agreement, it will resume its work on taxing the digital economy.

UN Model Convention

Recently, the United Nations has added a special provisions for income from automated digital services to the UN Model Tax Convention (see Article 12B), which would apply to treaty parties who agree to its inclusion.[35]

Unilateral DSTs[36]

Since the European Commission was unable to reach an agreement on an EU-wide DST, several European countries have decided to move forward with DSTs unilaterally. In addition, countries outside of Europe have also moved toward DSTs. While each country’s DST is unique in its design, most have adopted several elements from the EU’s DST proposal. Austria, Canada, France, India, and the United Kingdom are examples of countries that have implemented DSTs with various design elements.

Austria

Effective January 2020, Austria implemented a DST. The new digital advertising tax applies at a 5 percent rate on revenue from online advertising provided by businesses that have worldwide revenues exceeding €750 million ($801 million) and Austrian revenues exceeding €25 million ($27 million).[37] As Austria’s DST is only levied on online advertising, its scope is narrower than, for example, the DSTs in France or the UK.

Traditional advertisement is subject to a special advertisement tax in Austria.[38] One can argue that the DST thus levels the playing field between traditional and digital advertisement. However, the DST’s global and domestic revenue thresholds effectively exclude most domestic providers of digital advertisement, creating new distortions.

The DST was expected to raise €25 million ($27 million) in 2020, climbing to €34 million ($36 million) in 2023. The revenue raised in 2023 compares to 0.33 percent of corporate tax revenues and 0.02 percent of total tax revenues raised in 2018.[39]

Canada

Canada is the most recent entrant into the DST scene with a 3 percent rate on revenues from online marketplaces, social media platforms, sale and licensing of user data, and online ads with at least EUR 750 million (USD 801 million) in total annual worldwide revenues and Canadian revenues of CAD 20 million (USD 15 million).

The tax would be calculated on Canadian in-scope revenues for any calendar year that exceeds CAD 20 million. The policy has been adopted but has not yet been implemented.

France

France introduced its DST in July 2019, retroactive to January 2019. The DST imposes a 3 percent levy on gross revenues generated from digital interface services, targeted online advertising, and the sale of data collected about users for advertising purposes.[40] Companies will be in scope if they have both more than €750 million ($801 million) in worldwide revenues and €25 million ($27 million) in French revenues. The tax was estimated to generate €500 million ($533 million) annually—1.01 percent of France’s corporate income taxes and 0.05 percent of total tax revenue collected in 2018.[41]

India

Effective from June 2016, India introduced an “equalization levy,” a 6 percent tax on gross revenues from online advertising services provided by nonresident businesses.[42] As of April 2020, the equalization levy expanded to apply a 2 percent tax on revenues of e-commerce operators[43] that are nonresident businesses without a permanent establishment in India and are not subject to the already existing 6 percent equalization levy. The annual revenue threshold is set at INR 100,000 (USD 1,198).[44]

The change essentially expands the equalization levy from online advertising to nearly all e-commerce done in India by businesses that do not have a taxable presence in India, making it a much broader tax than the European DSTs described above and explicitly exempting domestic businesses.

United Kingdom

The UK’s DST became effective in April 2020,[45] with the first payment due in April 2021.[46] The tax is levied at a rate of 2 percent on revenues from social media platforms, internet search engines, and online marketplaces. Unlike other proposals, the tax includes an exemption for the first GBP 25 million (USD 31 million) of taxable revenues and provides an alternative DST calculation under a “safe harbor” for businesses with low profit margins on in-scope activities. The revenue thresholds are set at GBP 500 million (USD 623 million) globally and GBP 25 million (USD 31 million) domestically.[47]

The tax was expected to raise GBP 275 million (USD 342 million) in the fiscal year 2020-21 and GBP 440 million (USD 548 million) in the fiscal year 2023-24.[48] The fiscal year 2023-24 revenue estimate constitutes 0.06 percent of total tax revenue and 0.72 percent of corporate tax revenue in 2018.

Nevertheless, according to the UK National AuditA tax audit is when the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) conducts a formal investigation of financial information to verify an individual or corporation has accurately reported and paid their taxes. Selection can be at random, or due to unusual deductions or income reported on a tax return.

Office in the fiscal year 2021-2022, the DST collected GBP 358 million in revenue, 30 percent more than forecasted. Additionally, the DST paid was roughly equal to the amount of corporate tax paid by the business groups liable for DST and roughly one-tenth of the amount of VAT collected by the same companies. Five groups of the 18 business groups paying the DST paid 90 percent of the total revenue collected.[49]

Overview of DSTs in Europe

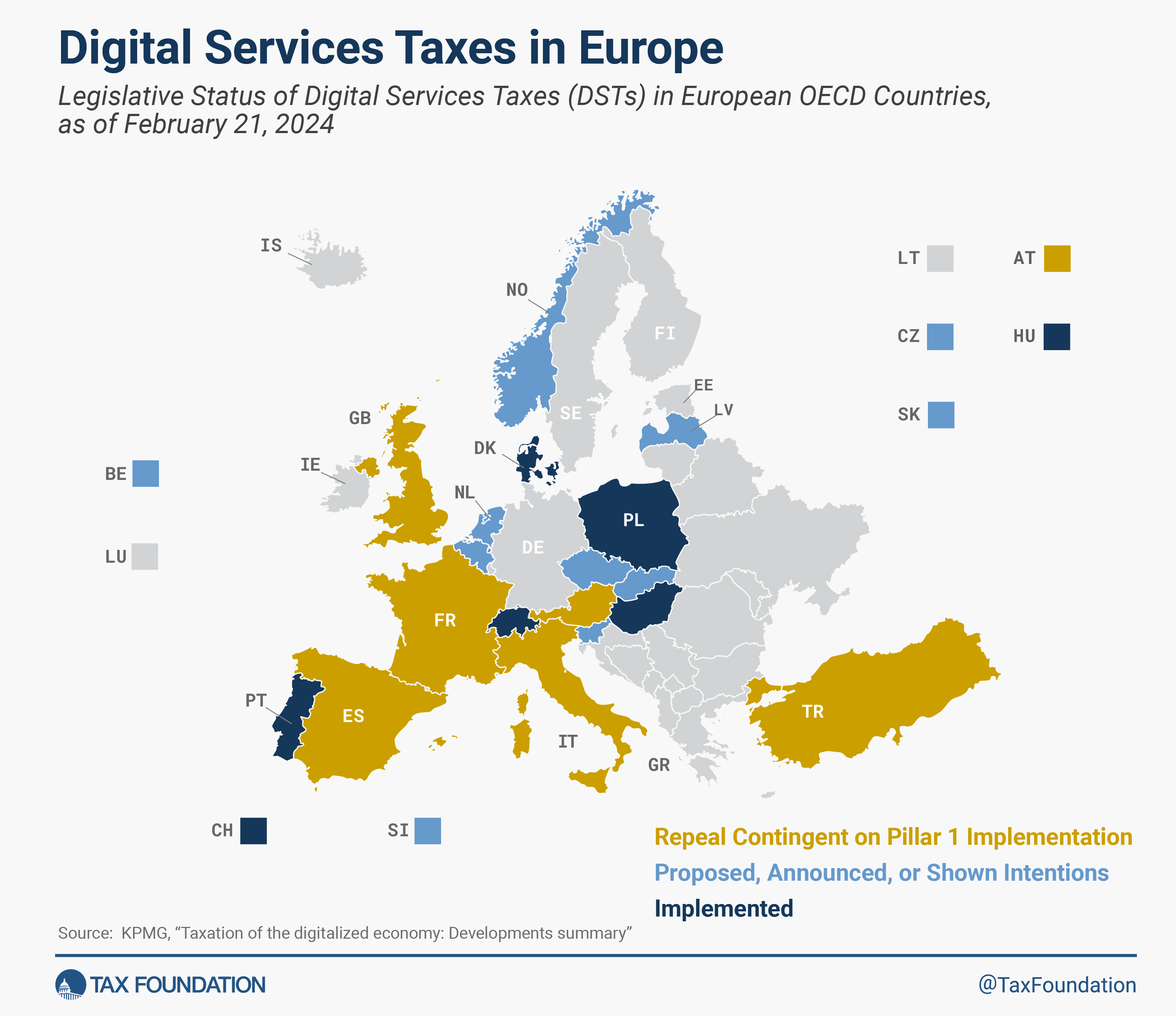

About half of all European countries have either announced, proposed, or implemented a DST. As of April 2024, Austria, Denmark, France, Hungary, Italy, Poland, Portugal, Spain, Switzerland, Turkey, and the United Kingdom have implemented a DST. Belgium and the Czech Republic have published proposals to enact a DST, and Latvia, Norway, Slovakia, and Slovenia have either officially announced or shown intentions to implement such a tax.

Overview of DSTs outside of Europe

Although most prevalent in Europe, DSTs have also been announced, proposed, or implemented in other regions of the world. Colombia, India, Kenya, Nepal, Sierra Leone, Tanzania, and Tunisia have all implemented DSTs. New Zealand proposed a DST, and Canada’s DTS is about to be implemented.

Economic Incidence of DSTs

The economic incidence of a DST is likely to be closer in nature to an excise taxAn excise tax is a tax imposed on a specific good or activity. Excise taxes are commonly levied on cigarettes, alcoholic beverages, soda, gasoline, insurance premiums, amusement activities, and betting, and typically make up a relatively small and volatile portion of state and local and, to a lesser extent, federal tax collections.

than to a corporate income tax.[50] While the economic literature shows that the corporate income tax is largely borne by shareholders—with shareholder income disproportionately concentrated in higher-income households—excise taxes are usually borne by consumers through higher prices. As lower-income individuals consume a larger share of their income, excise taxes tend to be rather regressive.

The exact equity effects of a DST, however, depend on the ability to pass the tax on to consumers, the type of goods and services sold, and consumers’ responsiveness to the tax.[51] Evidence shows that some companies targeted by DSTs have passed the tax on to customers or consumers. Apple, Amazon, and Google (now Alphabet) passed on the UK’s 2 percent DST tax.[52] Google has a page explaining that a charge for the DST is added on in countries where ads are accessed.[53]

Retaliatory Measures

Following France’s adoption of the DST, the United States Trade Representative (USTR) opened a Section 301 investigation into whether the French DST was a discriminatory tax on U.S. businesses. The USTR subsequently opened investigations into DSTs in Austria, India, Italy, Spain, Turkey, the United Kingdom, and Canada.

Evidence suggests that DSTs fall disproportionately on U.S. firms. The USTR found that 75 percent of the French DST on advertising would be paid by two U.S. firms, Alphabet (formerly Google) and Meta (formerly Facebook). In the UK, 90 percent of the tax was paid by five firms which are likely largely or completely U.S. firms.[54] In 2020, the Trump administration announced 25 percent tariffs on $1.3 billion worth of trade with the European Union in response to the French DST.[55] These tariffs had a delayed implementation date and are currently still on hold while Pillar One is being considered.

DSTs and Their Design Issues

Unlike corporate income taxes, DSTs are levied on revenues rather than income, not taking into account profitability. This means that the tax will be owed regardless of whether a particular digital service is profitable in the jurisdiction levying the tax. Seemingly low tax rates of such turnover taxes can translate into high tax burdens.[56] For instance, a business with $100 in revenue and $85 in costs has a profit margin of $15—or 15 percent. A DST rate of 3 percent means the business is required to pay $3 in revenue tax (3 percent of $100 revenue), corresponding to a profit tax of 20 percent ($3 tax divided by $15 profit). This implies that the corresponding effective profit tax rates vary by profitability, disproportionately harming businesses with lower profit margins.

Turnover taxes can apply multiple times over the supply chain as—unlike in the case of value-added taxes—there is no built-in credit system for already paid taxes. Such tax pyramidingTax pyramiding occurs when the same final good or service is taxed multiple times along the production process. This yields vastly different effective tax rates depending on the length of the supply chain and disproportionately harms low-margin firms. Gross receipts taxes are a prime example of tax pyramiding in action.

can distort economic activity and magnify effective tax rates.[57] Unlike VATs, turnover taxes also do not exempt business inputs. DSTs may tax business inputs such as advertising and cloud computing.

In addition, DSTs are discriminatory in terms of firm size. The domestic and worldwide revenue thresholds result in the tax being solely applied to large multinationals. While this can ease the overall administrative burden (by exempting smaller firms from the regulatory burden), it also provides a relative advantage for businesses below the threshold and creates an incentive for businesses operating near the threshold to alter their behavior. Similarly, digital businesses are at a relative disadvantage to non-digital businesses operating in a similar field—e.g., online and traditional advertising.

The introduction of a DST also creates new administrative and compliance costs. Governments have to provide detailed guidelines of how the tax is calculated and remitted, and then administer and enforce it. At the same time, businesses are required to identify the location of users and determine their taxable base. Since not all DSTs are equally designed and administered, businesses have even higher compliance costs due to challenges of dealing with those differences. Due to the issues outlined above and to enhance the functioning of the European cross-border market, Europe replaced its turnover taxes with VATs in the 1960s.[58] The emergence of DSTs reintroduces the negative economic consequences of turnover taxes—a step back in terms of sound tax policy.

Gross-Based Withholding Taxes on Digital Services

Another tax policy tool that has been customized for the digital economy is gross-based withholding taxes. Withholding taxes are often used to tax cross-border transactions, especially between countries that share taxing rights under a tax treaty. Cross-border interest payments, dividends, and royalties commonly have their own applicable withholding tax rates.

Recent activity (again both unilateral and multilateral) has increased the scope for royalties taxation to include digital services. This has been done by explicitly expanding the definition of royalties to, in some cases, include payments for software.

These policies require a business in Country A to pay taxes in Country B at a set rate based on the gross amount of a transaction. For example, a business in Country A provides a software service to a client in Country B. Country B applies a 5 percent withholding tax on payments for software services to foreign businesses. When the client in Country B makes a payment to the business in Country A, 5 percent of that payment is required to be withheld for tax purposes.

In many cases, bilateral tax treaties significantly reduce or eliminate cross-border withholding taxes. When a withholding tax does apply, businesses can file a tax return to reconcile the difference between taxes paid on a gross basis relative to actual income. However, if the withholding tax applies when there is no income attributable to the withholding country (under current practices), filing an income tax return is less useful.

In a way, some governments use gross-based withholding taxes on digital businesses to substitute for corporate or consumption taxes. Because digital businesses are less likely to have local permanent establishments in all countries where they have sales, the gross withholding tax is used in place of defining a virtual permanent establishment and requiring a foreign company to collect and remit VAT or pay corporate income tax.

However, taxing gross revenues leads to higher marginal tax rates on lower-margin businesses or transactions. This makes gross-based withholding taxes clearly inferior, from an economic point of view, to taxing net income or final consumption.

Despite that, there are also administrative and enforcement challenges to defining virtual permanent establishments and applying VAT to remote sales. Some developing countries simply face a trade-off between gaining some revenue through a withholding tax regime (regardless of economic efficiency) and building policies for digital VAT or virtual permanent establishments. The more that countries opt for gross-based withholding taxes, however, the less efficient and transparent taxation of digital companies becomes.

Individual Country Approaches to Withholding Taxes on Digital Services

Gross-based withholding taxes on digital services have become more common in recent years with several small countries implementing policies that tax the gross amount of transactions in related digital services. These policies are like the digital services taxes mentioned previously, although the withholding taxes apply without regard to the size of a business and have a much broader scope.

Some examples include India, Kenya, Mexico, Pakistan, Peru, Slovakia, Taiwan, Thailand, Turkey, and Uruguay. The withholding tax rates range from 1 percent in India to 30 percent in Peru.

UN Model Treaty and Software Taxing Rights

A multilateral approach to gross-based withholding taxes on digital services has been occurring at the UN Tax Committee. In 2018, the committee released an amended model tax treaty to provide for withholding taxes on technical services income.[59] Technical services include those of a “managerial, technical, or consultancy nature.”[60]

Prior to this change, the UN model treaty allowed for countries to share taxing rights over income from royalties (the rights to use a licensed product or service). For example, if a business in Country A licenses a product for use by a customer in Country B and the business does not have a permanent establishment in Country B, the UN model tax treaty would let both Country A and Country B tax some portion of the related royalty income. Individual bilateral treaties can differ from the UN model, but the model is influential on many countries’ interpretation or drafting of tax treaties.[61] Other tax treaty models (e.g., the OECD model and the U.S. model) only allow for Country A to tax the income in that scenario.

The amended UN model treaty ushered in a new opportunity for countries to impose withholding taxes related to income generated from services in their jurisdiction in the absence of a local permanent establishment. The effort has been followed closely by discussions to treat software-related payments as royalties.[62]

Both the technical services amendment and the proposal to incorporate software income into the definition of royalties would allow countries to apply gross-based taxes on software payments.[63]

Gross-based taxation is designed to ignore net income calculations and, because of this, can result in high marginal tax rates. Broadening the scope of gross-based withholding taxes increases the likelihood that digital businesses will get caught by taxes in countries where they do not have permanent establishments and with little opportunity to reconcile gross-based taxation with their net income.

Corporate Taxation and the Digital Economy

Corporate tax systems have been evolving to respond to the digitalization of the economy. Some countries have changed their corporate tax rules to require digital businesses that do not have employees or operations in their country to pay taxes on the sales or other activities that take place there via the internet.

Multinational business models of digital companies interact with tax systems all over the globe. Because of this, corporate tax changes aimed at digital businesses can change not only taxes paid by the businesses but also the tax bases in other countries.

The rationale behind many proposals to tax digital businesses is to eliminate inequities that arise from businesses that do not have operations within a country’s borders but earn income from services provided there.

Attempts to address these issues come from individual countries and multilateral forums. Unilateral policies to change where a business pays tax directly impact whether that business is paying tax twice or whether another country’s tax base is infringed upon. Multilateral efforts have the potential to change the rules for multinational companies without resulting in double taxation.

As with DSTs, some corporate taxation approaches apply to gross income rather than net income. These policies are more distortive in nature than income taxes and can create high marginal tax rates.

Significant Economic Presence and Digital Nexus Standards

One key feature of corporate tax systems around the world is the legal identification of a local entity that is liable to pay taxes. Businesses and workers are generally required to pay taxes where they earn their income. The common standard for determining when a business is liable to pay tax in a country depends on whether that business has a permanent establishment there.

The permanent establishment could be identified by ongoing operations in the country with employees, sales representatives, or other activities.

For digital business models, some countries have been expanding their permanent establishment definitions to not only include businesses with physical operations in a jurisdiction but also those with sustained economic activity there through digital means.

This could include a company that has dedicated digital marketing and digital storefronts targeting customers in a country, or a business that passes certain thresholds for the level of sales or contracts in a country.

Proposals in Europe, Africa, and Asia have outlined multiple approaches for determining when a company that is providing digital goods or services into a country could be liable for paying corporate income tax.

However, when a country expands its tax base by redefining what constitutes a permanent establishment, this can result in double taxation or a redistribution of taxing rights. If countries worked together to redefine permanent establishment definitions, double taxation could be avoided.

Moving Alone Can Create Double Taxation

Consider a streaming business that has $100 million in taxable profits. The business has its headquarters and all its operations in Country A and millions of subscribers and users around the world. In this example, it does not matter whether the business earns its revenue from paid subscriptions or through other means.

Country B accounts for 20 percent of global users. Both countries have a 20 percent corporate income tax rate.

Under standard permanent establishment definitions, the company would owe $20 million in taxes to Country A.

However, if Country B adopts a digital permanent establishment definition without conferring with Country A, double taxation can occur. Country B could adopt a rule that requires businesses to pay income taxes based on the share of global users in the country. In that case, 20 percent of taxable profits would be taxed in Country B. However, Country A would continue taxing the business and ultimately 120 percent of the business’s income would be taxed.

To provide some relief from double taxation, Country A could offer a tax creditA tax credit is a provision that reduces a taxpayer’s final tax bill, dollar-for-dollar. A tax credit differs from deductions and exemptions, which reduce taxable income, rather than the taxpayer’s tax bill directly.

for taxes paid in Country B, but that would reduce Country A’s tax base.[64] If the countries are unable to resolve a dispute over the taxing rights, the business would be caught in the middle paying tax twice on the same income.

Moving Together to Avoid Double Taxation

The previous example shows how simple it can be for one country to change a policy that either erodes the tax base of another country or leaves a business paying tax twice. One way to solve this issue is to have multiple countries rewrite international tax rules together.

For example, a group of countries could work together to rewrite their tax treaties and domestic tax legislation to have additional digital permanent establishment rules alongside rules that ensure that double taxation does not occur.

If instead of Country B from the example being the only country taxing the streaming business based on its share of global users, imagine that five countries (A, B, C, D, and E) with 20 percent corporate income tax rates agree that taxation based on users is appropriate. To avoid double taxation, Country A provides a tax credit for taxes paid in the other countries; any amount paid in the other four countries reduces the amount paid in Country A.

The business now pays tax in five countries. In four countries, its tax liability is based on its share of users in those countries, and in Country A, the business is taxed on its profits as usual minus a tax credit for those taxes paid in the other countries. Country A’s tax share, by formula, also reflects its share of global users.

Such an approach has trade-offs, though. The exercise could be repeated in different ways, creating various winners and losers. Countries, like Country A, that give up some of their tax revenues under new rules might not choose to participate in the process, meaning countries like Country B (which stand to gain the most) would choose to act alone as in Scenario 2. This assumes that the streaming business would not stop providing services in Country B even in the context of double taxation.

However, if the economic risk of double taxation through unilateral action is high enough, both the countries that would gain tax revenues under the proposal and those that would lose might be willing to come to an agreement.

Another challenge that is not provided in the example is that countries B, C, D, and E may not agree that the share of global users is the right metric to use for changing tax liability. That disagreement could mean that the final formula includes various weights for users, employees, assets, sales, or other factors.

This sort of division of taxing rights is referred to as formulary apportionmentApportionment is the determination of the percentage of a business’ profits subject to a given jurisdiction’s corporate income or other business taxes. U.S. states apportion business profits based on some combination of the percentage of company property, payroll, and sales located within their borders.

and is used in some countries with sub-central corporate taxation, as in the United States and Canada.[65] However, even within those systems, particularly for the U.S., double taxation can still arise because of different apportionment factors and formulas used by different states.

How Are Countries Changing Their Rules for Permanent Establishments?

Like Country B in Scenario 2 above, several countries around the world have explored (and sometimes implemented) rules that redefine how they tax digital businesses using new definitions of permanent establishments. These have been done outside of a negotiation with other countries and include Belgium, India, Indonesia, Israel, Kenya, Nigeria, Pakistan, Romania, Saudi Arabia, and Slovakia.

Each country has taken a slightly different approach to defining when a digital business with customers or users inside its borders will be liable to pay corporate tax on income connected to those users.[66]

A proposal in Belgium, which stalled in 2019, closely reflects a broader European Union proposal on corporate taxation, with numeric and monetary thresholds defining when a business might be liable for corporate tax in Belgium even if it does not have physical operations there.

India’s approach represents one of the broader proposals to tax digital businesses using a significant economic presence standard. The policy applies to revenues from data and software downloads in India.

Nevertheless, in order to eliminate double taxation concerns that would be caused by the significant economic presence test for taxation, tax treaties will override the significant economic presence test. Currently, India has double tax treaties with 94 countries.[67]

Indonesia has a proposal similar to India but Indonesia also has a fallback policy that applies to digital businesses even if the digital permanent establishment definition does not apply. This policy allows Indonesia to tax the gross revenues of electronic transactions. However, although the law was enacted implementing regulation is still pending and waiting for a global solution.

Israel’s policy for establishing significant economic presence applies to businesses that are clearly trying to reach customers in Israel through a website. The policy was established in 2016 and includes criteria for content tailored to Israeli customers or users and a positive correlation between internet usage and Israeli users.

Kenya has adopted a tax on income accruing from digital marketplaces.

Nigeria will tax online business profits to the extent that there is profit that can be attributed to a significant economic presence in the country. A business with a gross turnover or income of over NGN 25 million (USD 21,562) from digital activities in Nigeria would be liable for paying taxes in the country.

Saudi Arabia has implemented a regime that deems a company to have a virtual service permanent establishment if it has contracts that last longer than 183 days (although the length of time can differ depending on the applicable tax treaty).

Slovakia adopted a policy requiring lodging and transport digital platforms to register as a permanent establishment. If a business chooses not to register, a 5 percent withholding tax applies.

Proposals for Multilateral Coordination

As mentioned above, when countries unilaterally expand their thresholds for taxing corporate income, instances of double taxation can arise. Unless countries clarify that tax treaties will be used to avoid double taxation, coordination is necessary.[68]

Several broad forums work to negotiate changes to international corporate tax rules including the OECD, the United Nations Tax Committee, and the European Union. The Platform for Collaboration on Tax, which includes the UN, International Monetary Fund, OECD, and World Bank, was established in 2016 to foster collective action on tax matters around the world.

With respect to digital taxation, significant work has been done by the EU and the OECD. Model tax treaty discussions at the UN have also ventured into digital taxation in recent years. The G24, a group of developing countries, has also prepared a comprehensive reform to international corporate taxation that also accounts for digital business models.[69]

The EU Proposal on Significant Digital Presence

In 2018, the EU proposed an approach to unifying taxation of large businesses among EU Member States that included rules for identifying a significant digital presence that would lead to taxable profits in a jurisdiction.[70] The threshold for establishing a significant digital presence in an EU Member State includes three criteria which apply on an annual basis:

- €700 million ($747 million) in revenues

- 100,000 users

- 3,000 contracts for digital services

A business that meets any one of these criteria would be liable to pay corporate income taxes within that EU country.

Attribution of digital businesses’ taxable profits would account for “economically significant activities,” including:

- Collection, storage, processing, analysis, deployment, and sale of user-level data

- Collection, storage, processing, and display of user-generated content

- Sale of online advertising space

- Making available third-party-created content on a digital marketplace

- Supply of any digital service not listed in points 1 through 4

The proposal was paired with a temporary digital services tax as mentioned previously. Both proposals have stalled, although they have influenced the efforts at the OECD discussed below.[71]

The G24 Proposal for Significant Economic Presence

Another proposal addressing corporate tax rules and permanent establishment thresholds for digital companies has come out of the G24.[72] The proposal was submitted to the OECD as part of the process that has resulted in a two-pillar approach, of which Amount A in Pillar One is discussed below.

The G24 proposal follows an option identified in the OECD’s final report on Action 1 of the Base Erosion and Profit ShiftingProfit shifting is when multinational companies reduce their tax burden by moving the location of their profits from high-tax countries to low-tax jurisdictions and tax havens.

(BEPS) project for revising nexus rules using a significant economic presence test.[73]

Following the OECD option in the 2015 report, the proposal identifies that taxable nexus in a jurisdiction could be determined based on:

- Revenue generated on a sustained basis

- The user base and the associated data input

- Volume of digital content

- Tailored marketing or promotion activities

Using these factors, the proposal suggests that a digital business with no physical activity in a jurisdiction could be deemed to have significant economic presence and taxed based on that presence.

The G24 suggests allocating taxable profits among countries based on the location of sales, assets, employees, and users. Reallocating taxing rights based on factors such as these would significantly shift where multinationals pay taxes relative to current practices.

The Evolution of Pillar One, Amount A

The G20 and OECD’s BEPS project’s first action item from 2013 was to address the tax challenges of the digital economy.[74] While the 2015 report on Action 1 analyzed various options for direct taxation (i.e., changes in the context of corporate taxes) it made very few affirmative recommendations on that subject. Instead, the report suggested that policies designed to address profit shifting may be sufficient to also allay concerns about the ability of digital firms to minimize their tax burdens and that targeted digital policies may not be required once profit shifting had been adequately addressed.[75]

The options for taxing digital companies were revisited in a 2018 Interim Report, again with few positive recommendations.[76] However, at that time several countries had adopted policies specifically aimed at the digitalization of the economy, including policies like those in India, Israel, and Saudi Arabia mentioned above. Additionally, a number of countries began to impose DSTs based on revenue rather than income. As part of the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), the United States also introduced two new regimes related to the taxation of intangible income, namely foreign-derived intangible income (FDII) and global intangible low-taxed income (GILTI).[77] GILTI shifted the U.S. tax code from taxing dividends from foreign subsidiaries to a tax aimed at intangible income of foreign subsidiaries in low tax jurisdictions. GILTI provides a 10.5 to 13.125 percent tax rate on earnings that exceed a 10 percent return on a business’s invested foreign assets. Any profits exceeding that ordinary 10 percent return are assumed to be connected to the returns to IP or profit shifting.

Since 2018, the OECD has been working on a proposal to “Address the Tax Challenges Arising from the Digitalization of the Economy.” Between 2018 and 2021, when Action 1 was formalized into the two-pillar approach, the nature of the OECD proposal changed considerably. Pillar One was originally aimed at digital companies that did not have a physical presence in market jurisdictions. In 2021, the final Pillar One proposal abandoned the focus on digital firms entirely and now applies to all firms, except financial and extractive businesses.

Pillar One, Amount A changes the rules for where companies pay taxes.[78] Currently, companies generally pay taxes on their profits based on where those profits are generated by employees, laboratories, manufacturing, or distribution facilities. Amount A entails a series of formulas to shift a portion of taxable profits away from jurisdictions where profits are booked currently—that is, where they are produced—and move them to jurisdictions where sales are made to final consumers.

The rules would initially impact companies with global revenues above €20 billion ($21.4 billion) and profitability above a 10 percent margin. The revenue threshold would be cut in half after a review in the seventh year of the policy.

The rules take 25 percent of profits above a 10 percent margin and allocate that share to jurisdictions according to the share of sales in jurisdictions around the world.

The rules include approaches for identifying final consumers even when a company is selling to another business in a long supply chain. The rules also allow companies to use macroeconomic data on final consumption expenditure to allocate taxable profits when the location of final customers cannot be identified.

The rules define both where taxable profits are moved to and where taxable profits are shifted from.

The jurisdictions that will give up taxable profits are split into different tiers according to the different ratios of profits to depreciationDepreciation is a measurement of the “useful life” of a business asset, such as machinery or a factory, to determine the multiyear period over which the cost of that asset can be deducted from taxable income. Instead of allowing businesses to deduct the cost of investments immediately (i.e., full expensing), depreciation requires deductions to be taken over time, reducing their value and discouraging investment.

and payroll in a particular jurisdiction. This approach ensures that jurisdictions with the highest levels of profitability (compared to depreciation and payroll) will be the first to give up taxable profits to the benefit of jurisdictions where final sales are made.

If implemented, Amount A would result in a tax on profits of multinational companies even where there is not a local permanent establishment and require significant new coordination, and perhaps new institutions, to minimize tax disputes and ensure that no more than 100 percent of taxable profits are taxed for any given business.

Winners and Losers of Amount A

Scenario 3 in the examples provided at the beginning of this section shows that changes in rules that impact where a business pays taxes have impacts on individual countries. In a similar vein, various publications assess which countries might gain or lose tax revenue under Amount A.

A 2021 study of the world’s 500 largest companies found that Pillar One would affect 78 companies, 37 of which are based in Europe.[79] Table 7 shows how Amount A would be distributed relative to each country’s participation in the world’s GDP and worldwide profits of the 500 largest companies. Although the United States accounts for only 24 percent of the world’s GDP, and 38 percent of worldwide profits of the largest corporations, the United States companies will bear 64 percent of Amount A. The report also finds that 45 percent of the Amount A allocation came from technological companies, 85 percent of which were U.S.-based corporations. Another study found that the U.S.-based companies will bear the brunt of Amount A but in a smaller portion. Only 56 percent of Amount A would come from U.S. businesses, representing 31 companies.[80]

A recent report from the U.S. Joint Committee on Taxation analyzed the revenue impact of Amount A on the U.S. federal receipts and concluded that the U.S. would suffer a net revenue loss. The report estimated three revenue loss scenarios: $0.1 billion, $1.2 billion, and $4.3 billion, with the preferred estimate being a $1.2 billion loss.[81]

The Future of Pillar One, Amount A and DSTs

To be implemented, Pillar One, Amount A would require a multilateral treaty. However, this multilateral tax treaty has not yet been finalized for various reasons.

The draft treaty has a scoring system that determines when the treaty has achieved enough signatories to be implemented. The key threshold is 600 points of 999 points available.[82] But the U.S. has been attributed 486 points, meaning that the threshold cannot be achieved without the U.S. Losing tax revenue is one good reason why the U.S. might not want to ratify this treaty.

Additionally, several countries have expressed objections to the draft proposal. Brazil, Colombia, and India object to a provision that suggests that current taxes applied in market countries should reduce the new opportunity to tax profits allocated under Amount A. If a country already has the right to tax a business on its activity in a country using withholding taxes, and Amount A would allocate new taxing rights, Amount A taxing rights should be reduced by existing rights to tax in a market jurisdiction.

A major reason for the negotiations leading to Pillar One, Amount A, was the possibility of eliminating DSTs. However, even with Amount A, countries may keep their DSTs anyway. The draft treaty includes a list of policies that should be removed once the treaty is adopted and includes eight countries that have implemented DSTs (currently 18 countries have implemented DSTs).[83] The draft also eliminates amount A allocation for countries that do not remove policies that fit the treaty’s definition of DSTs:

- The tax is driven by the location of customers or users.

- It is generally a tax on foreign businesses.

- It is not a tax on income and is beyond agreements to avoid double taxation.

Nevertheless, the countries that are not on the list could ponder under which system they are better off revenue-wise or work around the above principles. Additionally, five European countries have an agreement with the U.S. to reduce tax payments under Pillar One, Amount A in connection with the amount of taxes paid under a DST. This agreement is time-limited and will expire on June 30, 2024, unless further extended. [84]

Best Practices in Digital Corporate Taxation

Singling out the digital economy through specific means using corporate tax is fraught with challenges. Any rule changes in this policy area should be done through a multilateral process to avoid creating different standards that result in double taxation. However, among the unilateral efforts, some key points are valuable.

The Israeli approach clearly identifies links between a digital platform and the local economy and represents a reasonable attempt to identify a digital permanent establishment.

The proposals by multilateral forums generally suffer more from political challenges than policy challenges. While part of the motivation behind Amount A in Pillar One was to remedy current tax policy imbalances, Amount A might create additional ones. It is uncertain whether a robust system for allocating profits is achievable.

Both at the country level and at the international level, corporate tax policies should be designed without specific business models in mind. Otherwise, real distortions could arise. To the extent to which adjusting nexus rules specifically requires new definitions for the digital era, countries should provide clear guidance about when a virtual permanent establishment arises.

Deeming virtual permanent establishments unilaterally can create both uncertainty and double taxation.

Conclusion

In recent years, governments around the world have begun to adapt their tax systems to capture the digitalization of the economy. These efforts have led to changes in consumption taxes and corporate taxation. To ensure neutrality between digital and non-digital businesses, many countries have extended their VATs/GSTs to include digital services.

Most large digital businesses are multinational corporations, generating revenue streams from countries across the world. Concerns have been raised that the current international corporate tax system—with its traditional permanent establishment rules—does not properly capture these novel business models. This has led us to the ongoing OECD negotiations among more than 140 countries to adapt the existing international tax rules.

A significant number of countries have adopted unilateral tax measures targeted at digital businesses, including digital services taxes, gross-based withholding taxes, and digital permanent establishments. However, in the absence of a multilateral coordination, these targeted unilateral tax policies will continue to spread and mutate, resulting in uncertainty and double taxation.

As e-commerce continues to grow, many countries expanded the consumption tax to include digital services and products. This could achieve a neutral broadening of the tax base and additional tax revenue. As the digital economy continues to grow, so will VAT revenue from cross-border digital transactions, deeming other distortionary tax policies unnecessary.

The outcome of the digital tax debate will likely shape domestic and international taxation for decades to come. Designing these policies based on sound principles—simplicity, transparency, neutrality, and stability—will be essential in ensuring they can withstand challenges arising in the rapidly changing economic and technological environment of the 21st century.

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

Appendix

Appendix Table 3: Proposals for Digital Permanent Establishment Rules

| Jurisdiction | Description | Threshold for Digital Permanent Establishment | Current Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Belgium | Follows the EU Directive to include significant digital presence thresholds for determining corporate income tax liability | 1. Revenues associated with digital services exceed EUR 7 million (USD 7.5 million)

2. Number of associated users exceeds 100,000 3. Number of business contracts exceeds 3,000 |

Rejected by the Finance and Budget Committee in the Belgian Chamber of Representatives, March 2019; waiting for a global solution |

| India | Deems a permanent establishment in India for businesses that otherwise would not be local providers of digital goods or services | 1. Revenues arising from data or software downloads in India

2. Systematic and continuous activity soliciting business in India through digital means 3. The thresholds effective from 1 4. Revenue-linked condition: threshold of INR 20 million (USD 239,374) 5. User-linked condition: threshold of 300,000 Indian users |

Adopted, March 2020; applies since April 2022 |

| Indonesia | Deems a permanent establishment based on significant presence in the e-commerce economy of Indonesia

If the permanent establishment threshold is not met, then an electronic transactions tax would apply |

1. Consolidated growth revenues

2. Sales amounts in Indonesia, and/or |

Adopted, March 2020; although the law was enacted, implementing regulation is still pending and the country is waiting for a global solution |

| Israel | Deems a permanent establishment in Israel for a nonresident company | 1. Online services are provided to many Israeli customers

2. Substantial number of transactions with Israeli customers 3. Positive relationship between online earnings and level of internet usage of Israeli users 4. Tailored online services to Israeli users (Hebrew language website or pricing is in shekels) |

Adopted, April 2016 |

| Kenya | Charges tax on income accruing from a digital marketplace | Income accruing through a digital marketplace (a platform that enables the direct interaction between buyers and sellers of goods and services through electronic means) | Adopted, November 2019 |