If reelected, President Trump would drastically escalate the trade war he started during his first term, with proposals for new 10 percent universal baseline tariffs and 60 percent tariffs on imports from China. But what often goes unnoticed is President Biden’s role in continuing President Trump’s first trade war. In fact, more taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities.

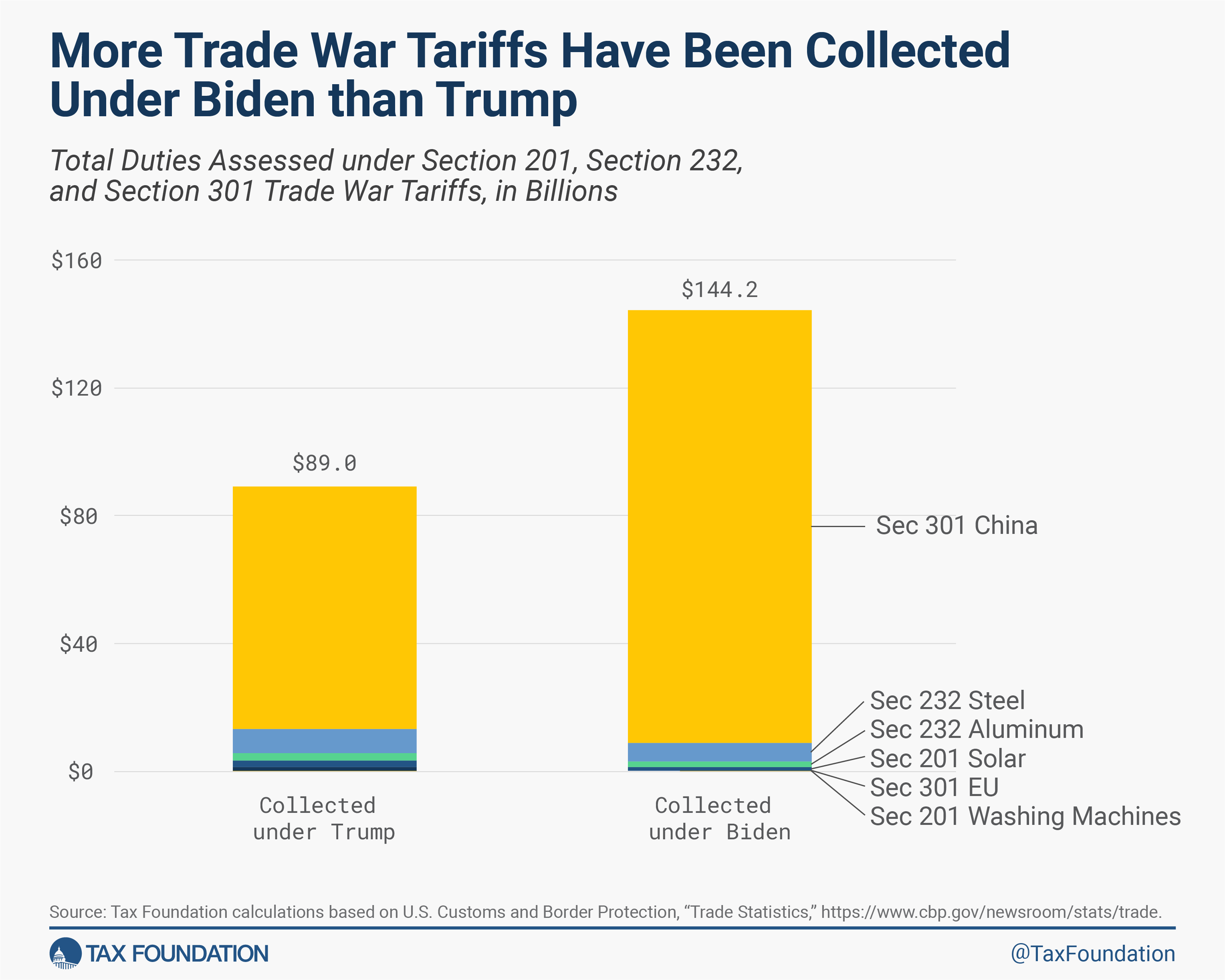

revenue from the trade war tariffs has been collected under Biden than under Trump.

Trump instigated a trade war by imposing new tariffs (taxes) on imports of washing machines and solar panels (Section 201), steel and aluminum (Section 232), and billions of dollars’ worth of consumer, intermediate, and capital goods from China (Section 301) throughout 2018 and 2019. Based on levels of trade before the tariffs went into effect, the new levies amounted to a tax increase of $80 billion a year. Outside of allowing the washing machines tariffs to expire in 2023 and some narrow modifications to the steel and aluminum tariffs and solar panel tariffs, President Biden has kept nearly all Trump tariffs in place.

While the static analysis indicates the tariffs amount to an $80 billion a year tax increase, trade levels have not remained the same since the tariffs went into effect. Broadly speaking, trade has fallen in the categories of goods subject to tariffs and has increased in the categories (or from other jurisdictions) not subject to tariffs. Accordingly, since they were imposed, the trade war tariffs have raised customs duties collections by around $233 billion through March 2024.

Of that $233 billion, just $89 billion was collected during the Trump administration. The remaining $144 billion has been collected during the Biden administration.

The vast majority of the increase in tax collections has come from the Section 301 tariffs on goods from China—$211 billion of the $233 billion. While political rhetoric claims the tariffs have been paid by China and other foreign countries, they are actually paid by people in the U.S. importing foreign goods. And the economic burden of those higher tax payments has fallen almost exclusively on American consumers in the form of higher import or retail prices.

The billions in added tax costs for Americans are not the only harm from the trade war. Far worse is that the 2018-2019 tariffs have had a net negative impact on the U.S. economy, a consensus that emerges from the economic literature on the trade war. Here’s a sampling of the findings:

- Federal Reserve economists Aaron Flaaen and Justin Pierce estimated the effects of the tariffs on the U.S. manufacturing sector accounting for both the benefits of tariffs to protected companies and the costs of tariffs to companies that faced higher input prices or other distortions. On net, they found a decrease in manufacturing employment due to the tariffs: the positive contribution from protected industries was significantly outweighed by the effects of rising input costs and by retaliatory tariffs.

- Louis Federal Reserve economists Ana Marie Santacreu and Makenzie Peake evaluated how exposure to trade at the onset of the trade war was correlated with employment and output growth to evaluate the effects of changing U.S. trade policy. Their empirical analysis shows that states more exposed to U.S. tariffs on imports from China experienced lower increases—or even decreases—in employment and output, providing additional evidence that exposure to tariffs played a role in reductions in employment and output.

- Economist David Autor and coauthors found the tariffs did not raise U.S. employment in protected sectors while retaliatory tariffs had “clear negative employment impacts.”

- A May 2023 report from the United States International Trade Commission (USITC) estimated the effects of steel and aluminum tariffs on a subset of affected industries and found an annual average $2.8 billion production increase enabled by the higher prices from the tariffs was met with an annual average $3.4 billion production decrease in certain downstream industries. This highlights a pattern of gains for protected industries that were more than offset by losses for downstream industries.

Despite the higher costs falling on American consumers and the harms to U.S. employment and production—particularly in the manufacturing sector—both the Trump campaign and the Biden administration have continued to defend the trade war tariffs. That’s likely a reflection of the gap between economic reality (the tariffs have on net harmed Americans and made us poorer) and the political messaging (which claims the tariffs hurt foreigners and help Americans).

Reelecting President Trump would clearly entail billions more in added annual tax costs from higher tariffs, which would invite significantly worse economic distortions and losses than the initial trade war. At the same time, it remains unclear how reelecting President Biden would alter the course of the trade war. The Biden administration has still not published the findings of its statutory review of the Section 301 tariffs on China, though it is expected to retain most of the tariffs. Unfortunately, when it comes to the trade war tariffs, it seems both candidates support higher taxes on American consumers and the increased economic distortions that follow.

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

Share