If there’s one thing that unites Oregonians, it’s opposition to sales taxes. Since ratifying a constitutional amendment prohibiting a sales taxA sales tax is levied on retail sales of goods and services and, ideally, should apply to all final consumption with few exemptions. Many governments exempt goods like groceries; base broadening, such as including groceries, could keep rates lower. A sales tax should exempt business-to-business transactions which, when taxed, cause tax pyramiding.

in 1910, Oregonians have rejected sales taxes at the ballot 10 times—and the only times the opposition dipped below 70 percent was when a pair of 1990 advisory measures floated the elimination of school property taxes.

Now, Oregonians are being asked to approve the most extreme sales taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities.

proposal yet, one that applies to the same purchase multiple times and could easily yield double-digit rates of tax. But precisely because of this outlandish design, many Oregonians may not recognize it for what it is: the nation’s most aggressive sales tax (and worse).

Measure 118 is presented as a tax on large corporations, but that’s semantics, and not much different than saying that retail sales taxes are levied on retail businesses. Consumers know they pay the sales tax. They’ll bear much of the incidence of the tax created by Measure 118 too. Not all (and in some ways the consequences of the rest of the tax burden are even more undesirable), but a lot of it. Enough for Measure 118 to count as a far higher sales tax than any of the 10 retail sales taxes that voters rejected between 1993 and 1993.

The tax created by Measure 118 is a 3 percent tax on the gross revenue of large corporations. It sounds like a classic tax on big business, but it functions like an aggressive sales tax on consumers.

Corporations are subject to corporate income taxes on their profits (net income). Oregon is also unusual in imposing a minimum tax on corporations that don’t have much taxable incomeTaxable income is the amount of income subject to tax, after deductions and exemptions. For both individuals and corporations, taxable income differs from—and is less than—gross income.

in a given year, either because they experienced losses, had major expenses (like significant new capital investment), or, sometimes, because they benefitted from state tax incentives. Under Measure 118, the current minimum tax is replaced with a 3 percent gross receipts taxA gross receipts tax, also known as a turnover tax, is applied to a company’s gross sales, without deductions for a firm’s business expenses, like costs of goods sold and compensation. Unlike a sales tax, a gross receipts tax is assessed on businesses and apply to business-to-business transactions in addition to final consumer purchases, leading to tax pyramiding.

. Most businesses would pay that minimum tax rather than the existing net income tax, since the minimum tax will almost always be the greater tax.

If, for instance, a company had $50 million in Oregon-apportioned gross incomeFor individuals, gross income is the total pre-tax earnings from wages, tips, investments, interest, and other forms of income and is also referred to as “gross pay.” For businesses, gross income is total revenue minus cost of goods sold and is also known as “gross profit” or “gross margin.”

, of which $4 million was profits, it would owe $294,000 under the current income tax (with marginal rates of 6.6 and 7.6 percent) imposed on $4 million in net income. But under a 3 percent tax on its gross income of $50 million, the company would pay $1.5 million—an effective rate of 37.5 percent on profits.

In practice, when the tax is imposed at the level of final sale, it’s essentially the equivalent of a 3 percent sales tax on that transaction. Because all large businesses (most grocery stores, big box retailers, tech companies, etc.) face the same tax on sales into Oregon, most, if not all, of this cost will be passed along to consumers.

If that were the end of it, the tax might not be so bad. It would still be akin to the many sales taxes Oregon voters have routinely rejected, but most states have sales taxes, and 3 percent is a low rate for a sales tax.

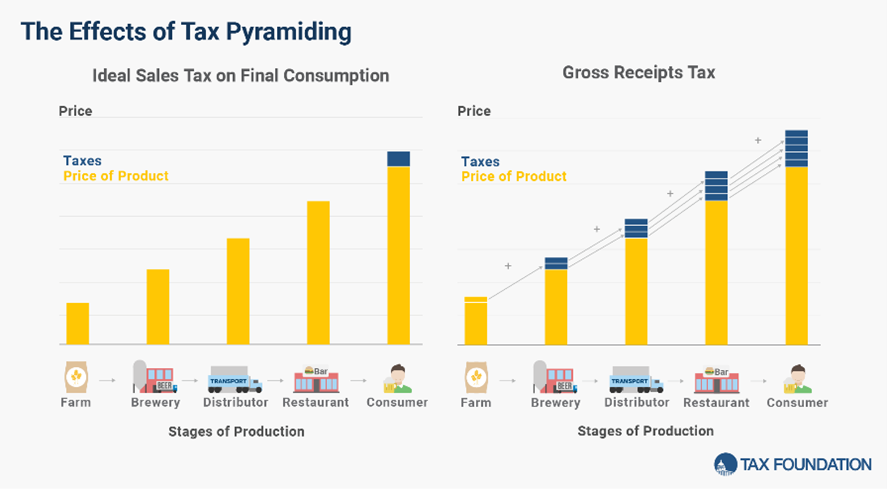

Unfortunately, this sales tax isn’t just imposed at the retail level. It’s also imposed on the same product at the wholesale level, and at each stage of the manufacturing process. The tax is embedded at every level of production.

This creates incentives for businesses to do as much of their production as possible outside Oregon borders, which is bad for Oregon’s economy. When businesses can’t do that, or there are significant additional costs associated with out-of-state manufacture or purchase, much of the added cost will be embedded in the final price that consumers pay, a process known as tax pyramidingTax pyramiding occurs when the same final good or service is taxed multiple times along the production process. This yields vastly different effective tax rates depending on the length of the supply chain and disproportionately harms low-margin firms. Gross receipts taxes are a prime example of tax pyramiding in action.

.

In Washington, which has long levied a gross receipts tax (the retail rate is 0.471 percent, far lower than the 3 percent rate planned in Oregon), revenue officials estimate average statewide pyramiding of four times the statutory tax rate—meaning that a 0.471 percent rate is about the same as a 1.88 percent sales tax, since it gets embedded multiple times across the production chain.

If that level of pyramiding held in Oregon, consumers could expect to see about a 12 percent price increase. It may not show up on the receipt, but make no mistake: that’s like a 12 percent sales tax, in a state with an aversion to sales taxes.

The tax would also be regressive, since the highest effective rates are on consumer goods (where profit margins are often slim) and the lowest effective rates are in areas like information services, where profit margins are often larger. The following chart looks at effective rates at a single stage of production for several different industry sectors, not even taking into account how many times the tax would pyramid for the goods and services provided by these industries. Typically, there are far more stages of production for retail goods than for services. Groceries, which have notoriously low margins, would be hit particularly hard.

Imagine going to a grocery store and buying a $10 frozen dinner. For that product to get to you, a farmer had to grow the crops or raise the livestock, a food processor had to turn it into a frozen dinner, a wholesaler had to facilitate getting it from the food processor to your local grocery store, and your grocer had to staff a store at which you could purchase it. Each stage of this process—and many more transactions (seed, fertilizer, fodder, agricultural equipment, delivery fleets, etc.)—could be subject to the tax, depending on the size of the businesses involved and whether the transaction takes place in Oregon.

For our example, we’ll draw on a national dataset about gross and net profit margins by industry. Retail grocery stores, for instance, have average net profit margins of 1.18 percent, but gross margins of 25.54 percent. This means that 25.54 percent of grocery stores’ sales revenue is above and beyond the amount they paid wholesalers for products. This does not, however, mean that they pocketed 25.54 percent, because they have operating expenses: employees’ salaries, rent, utilities, and all the other expenses of running a store. At the end of the day, they net 1.18 percent profit—which makes a 3 percent tax on gross revenue a very big deal, because it’s two and a half times their profit.

The gross revenue numbers, however, allow us to work back to see prices for a typical agricultural product at each stage. Without tax, a farmer is paid $4.78 on gross costs of $4.00, then a food processor generates an additional $1.56 for turning the crops into a consumer good, then the wholesaler generates another $11.11, and the retailer $2.55, for a final consumer price of $10.00. Notably, while the increments seem large—the retailer makes $2.55 above purchase price, for instance—their margins are small because most of the difference is operating costs. The farmer has the highest net profit margins at 7.12 percent, followed by the food processor at 6.0 percent. The wholesaler and retailer, despite significant gross revenue, have high operating costs and net only 1.21 and 1.18 percent profit, respectively.

But gross receipts taxes do not care about profit margins. They care about gross revenue, and the tax applies—at 3 percent—at every stage where a transaction involves a large business.

While large-scale national farming operations exist and have significant market share, we will assume that the farm operator is well below the threshold for liability under the new tax, though half of their costs (agricultural equipment, seeds, etc.) come from companies liable for the tax. The other stages—food processing, wholesale, and retail—are assumed to be subject to the tax.

The result? A 3 percent gross receipts tax results in $1.09 in tax embedded in what had been a $10 transaction—the equivalent of a 10.9 percent sales tax. Pre-tax profits on the entire transaction, across all stages of production, were just under 5 percent (49.6 cents on $10), meaning that the tax is 220 percent of pre-tax profits. Most of the cost has to be shifted to consumers; it literally can’t come out of profits.

Measure 118 is supposed to raise money for taxpayer rebate checks, which may seem attractive. But when it’s understood that the money comes from what is effectively a high rate and highly distortionary sales tax, it comes across as a much worse deal.

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

Share