Key Findings

- The sales taxA sales tax is levied on retail sales of goods and services and, ideally, should apply to all final consumption with few exemptions. Many governments exempt goods like groceries; base broadening, such as including groceries, could keep rates lower. A sales tax should exempt business-to-business transactions which, when taxed, cause tax pyramiding.

is the second-largest source of state taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities.

revenue and an important source of local tax revenue, but decades of base erosion threaten the tax’s share of overall revenue and have prompted years of countervailing rate increases. - A well-designed sales tax is more stable and economically efficient than most potential tax alternatives, except taxes on real property.

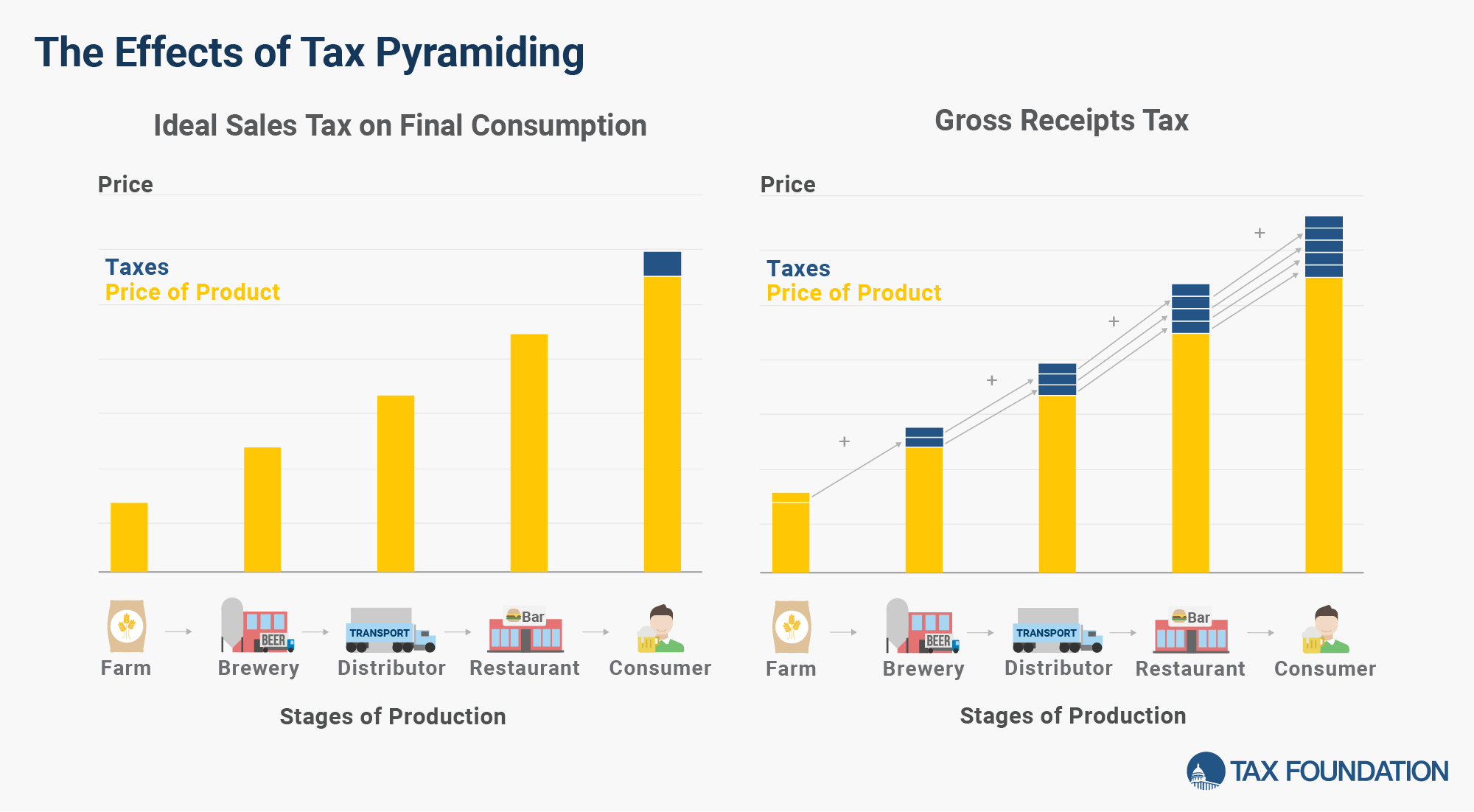

- The taxation of intermediate transactions (business inputs) can turn that portion of the sales tax into a tax on production, driving up consumer prices through tax pyramidingTax pyramiding occurs when the same final good or service is taxed multiple times along the production process. This yields vastly different effective tax rates depending on the length of the supply chain and disproportionately harms low-margin firms. Gross receipts taxes are a prime example of tax pyramiding in action.

and discouraging in-state capital investment. - Economic analysis supports employing a broad definition of business inputs for the purposes of excluding them from the base.

- Policymakers should explore sales tax base broadeningBase broadening is the expansion of the amount of economic activity subject to tax, usually by eliminating exemptions, exclusions, deductions, credits, and other preferences. Narrow tax bases are non-neutral, favoring one product or industry over another, and can undermine revenue stability.

to certain excluded goods and services (including newly arising digital products), particularly as an offset for tax relief elsewhere, but should be careful about overly broad inclusions that fall largely on intermediate transactions, as these changes can prove significantly more harmful than the taxes they were intended to offset. - States have significant room to reduce compliance costs for remote sales.

- The United States is an outlier in the distortions within state-level consumption taxes, and simplifying, pro-growth reforms are overdue.

Introduction

By any measure, sales taxes matter. Sales taxes account for 30.4 percent of all state tax revenue, second only to individual income taxes (37.7 percent),[1] and are a meaningful source of local tax revenue as well, albeit a distant second behind property taxes. They win high marks for their stability and economic efficiency, but are often criticized for their complexity for remote sellers and potential regressivity, both real and perceived.

Nearly a century into the history of state sales taxes, moreover, interest in them is coming full circle. The first state sales taxes were adopted during the Great Depression to augment state revenues as property values, and hence property taxA property tax is primarily levied on immovable property like land and buildings, as well as on tangible personal property that is movable, like vehicles and equipment. Property taxes are the single largest source of state and local revenue in the U.S. and help fund schools, roads, police, and other services.

collections, plummeted. (At the time, property taxes were the predominant source of state, not just local, tax collections.)[2] Today, an emerging focus on raising sales tax rates, broadening sales tax bases, or both is increasingly being driven by a desire to fund property tax relief in the face of rapidly appreciating assessments.

This impetus—which has its apotheosis in a series of proposals in Nebraska, North Dakota, and Wyoming throughout 2024 but is playing out throughout the country[3]—is not, of course, the only reason policymakers have taken a renewed interest in the sales tax.

Because well-designed sales taxes are more pro-growth than taxes on income, some tax reformers have sought additional sales tax revenue to pay down income tax rate reductions. Because today’s economy looks vastly different from the economy of a decade ago, to say nothing of nearly a century ago, other reformers have sought to modernize sales tax codes to capture new modes of consumption, reversing years of base erosion. And because an ever-growing number of transactions take place online, and many of them involve digital rather than tangible (physical) products, still others are exploring reforms to reduce compliance costs, or—moving in a different direction—to broaden the base to additional non-consumption categories.

This publication is intended as a guide for policymakers looking at the sales tax anew, addressing:

- Key principles of sales taxation on which public finance experts widely agree

- The possible scope of taxable personal consumption

- The economic literature on the effects of taxing business inputs

- Appropriate definitions of business inputs

- Approaches and cautions on the taxation of digital products

- The sales taxation of products separately taxed under an existing excise taxAn excise tax is a tax imposed on a specific good or activity. Excise taxes are commonly levied on cigarettes, alcoholic beverages, soda, gasoline, insurance premiums, amusement activities, and betting, and typically make up a relatively small and volatile portion of state and local and, to a lesser extent, federal tax collections.

regime - The policy implications of current sales tax exemptions

- The economic effects of sales taxes compared to other tax revenue options

- Important design considerations for a well-functioning sales tax

General Principles of Sales Taxation

The sales tax is, for the most part, a good tax. Taxes on consumption are more economically efficient than taxes on income (though less efficient than taxes on real property), meaning they do less to distort economic decision-making; do less to reduce investment levels and labor force participation; and are less likely to adversely affect interstate migration. This holds true not just in the realm of an ideal consumption taxA consumption tax is typically levied on the purchase of goods or services and is paid directly or indirectly by the consumer in the form of retail sales taxes, excise taxes, tariffs, value-added taxes (VAT), or an income tax where all savings is tax-deductible.

, but more importantly in the real-world case of the sales tax as it exists in US states, even though these taxes substantially depart from what public finance scholars would consider an “ideal” sales tax.[4]

In the real world in which policymakers operate, few taxes will ever achieve their “ideal” form. Nevertheless, reforms that move the sales tax closer to those ideals will improve tax competitiveness and create opportunities for economic growth, while shifts in the other direction can render the sales tax more economically harmful than taxes to which it is commonly held to be economically superior.

In particular, the ideal sales tax is a tax on final consumption. Yet, to varying degrees, a substantial portion of the sales tax in each state falls on the factors of production instead. A tax on consumption is more pro-growth than an income tax, but a tax on production is worse than an income tax. In the real-world case of sales taxes that fall on both consumption and production, the analysis is dependent upon the preponderance of those burdens.

Public finance scholars disagree on many things, including some of the finer points of sales taxation, but the following seven principles and observations capture the broad consensus of public finance scholars who study sales taxation.[5] Key elements of this consensus will be explained further later, and are supported by the academic literature cited throughout. In short:

- An ideal sales tax is imposed on all final (personal) consumption, both goods and services.

- An ideal sales tax exempts all intermediate transactions (business inputs) to avoid tax pyramiding and to avoid transforming it from a consumption tax to a tax on production or investment.

- Sales taxes should be destination-based, meaning the tax is owed in the state and jurisdiction where the good or service is consumed.

- The sales tax is more economically efficient than many competing forms of taxation, including the income tax, because it only falls on present consumption, not savings or investment.

- Because lower-income individuals have lower saving rates and consume a greater share of their income, the sales tax can be regressive, though broader bases that include consumer services (much more heavily consumed by higher-income individuals) push in a progressive direction.

- The sales tax scales well with the ability-to-pay principle because it grows with consumption and is therefore more discretionary than many other forms of taxation.

- Consumption is a more stable tax baseThe tax base is the total amount of income, property, assets, consumption, transactions, or other economic activity subject to taxation by a tax authority. A narrow tax base is non-neutral and inefficient. A broad tax base reduces tax administration costs and allows more revenue to be raised at lower rates.

than income, though the failure to tax most consumer services in many states is leading to a gradual erosion of sales tax revenues as services become an ever-larger share of consumption.

Unfortunately, real-world sale taxes not only fall short of these ideals, but are, in some ways, getting worse. Sales tax breadth has narrowed in recent years as personal services (largely exempted) have grown as a share of final consumption and lawmakers have continued to carve out existing tax bases. In response to this base erosion, many state lawmakers have not modernized their codes to include a wider range of consumer goods, as might be hoped, but have rather focused on categories that overwhelmingly consist of intermediate transactions, like business digital goods and services—a particularly attractive target, but one that threatens to harm states’ economic competitiveness. And where lawmakers have not been able to arrest base erosion, they have instead turned to rate increases on ever-narrower bases, the inverse of the well-known maxim of broad bases and low rates.

The following table shows states’ weighted average sales tax rates, reliance (share of all tax revenue raised from the general sales tax), and breadth measured as a percentage of state personal income, for both fiscal years 2000 and 2022. Clearly, rate increases have offset the erosion of sales tax bases.

Under a different set of calculations that defines sales taxes more narrowly,[6] we find that in the late 1970s, sales tax bases captured 45 percent of personal income. By the 2010s, this figure had been reduced by more than a third, with bases hovering between 29 and 31 percent of personal income for 13 years before experiencing a slight uptick in 2022, the dual consequence of pandemic-induced shifts in consumption patterns and greater compliance from remote sellers as more states implemented and ramped up enforcement of remote seller and marketplace facilitator laws in the aftermath of the Supreme Court’s decision in South Dakota v. WayfairSouth Dakota v. Wayfair was a 2018 U.S. Supreme Court decision eliminating the requirement that a seller have physical presence in the taxing state to be able to collect and remit sales taxes to that state. It expanded states’ abilities to collect sales taxes from e-commerce and other remote transactions.

, Inc. (2018), discussed later.

In the absence of base-broadening reforms, states have instead resorted to rate increases to maintain the sales tax’s share within the tax base, as indicated earlier, with the weighted average state-level sales tax rate rising from 4.19 percent in 1977 to 6.0 percent in 2023, peaking at 6.16 percent in 2010.

Economic Implications of Sales Taxation

All taxes are not created equal. Any tax creates a certain amount of economic drag; this is unavoidable. There is truth to the adage that “whatever you tax, you get less of”—so it makes sense for policymakers to think carefully about what they choose to tax, and how. Individual income taxes fall on labor; on the margin, they lower the payoff to work, decreasing the supply of labor while increasing its cost.

An income tax can be conceptualized as a tax on consumption plus the change in savings, while a well-structured sales tax is a tax on income less the change in savings. An income tax reduces the capacity for future consumption; economically, it acts like a sales tax that increases the cost of future consumption, with each additional hour of labor producing fewer goods in the future. Consumption taxes are much more economically neutral by comparison, and the economic literature consistently finds that sales taxes are less of an impediment to economic growth or location decisions than income taxes.[7]

One major study, involving data from 21 OECD countries from 1971 to 2004, found that a 1 percent shift of tax revenues from income taxes (both individual and corporate) to consumption taxes would increase gross domestic product (GDP) per capita by 0.74 percent in the long run.[8] (Property taxes are even more economically efficient, with a shift from income to real property taxes increasing GDP by 1.45 percent, indicating that policymakers should be wary of replacing property tax revenues with other taxes, including sales taxes.)[9]

And while studies frequently find that reduced rates of income taxation increase GDP,[10] upward mobility,[11] employment,[12] investment rates,[13] and innovation,[14] they generally fail to identify similarly salient effects for consumption tax rates,[15] or, in the case of at least one international study, even found the opposite effect. A study of Canadian provinces found that raising the sales tax rate increased growth, evidently because the rate increases undercut the impetus for economically inferior taxes on investment.[16]

Sales taxes are typically destination-sourced, meaning that they are taxed where a good or service is consumed, not where it is produced. Thus, unlike income taxes, they do not inherently discourage investment or job creation.[17] This is, however, only true insofar as the tax falls on final consumption; when the tax falls on business inputs, it increases the cost of investing in-state. Business input taxation reduces capital investment and gross state product,[18] and may make the economic incidence of the sales tax more regressive because tax pyramiding is more concentrated within tangible goods that comprise a greater share of low earners’ consumption.[19] These effects are given more consideration in the pages that follow.

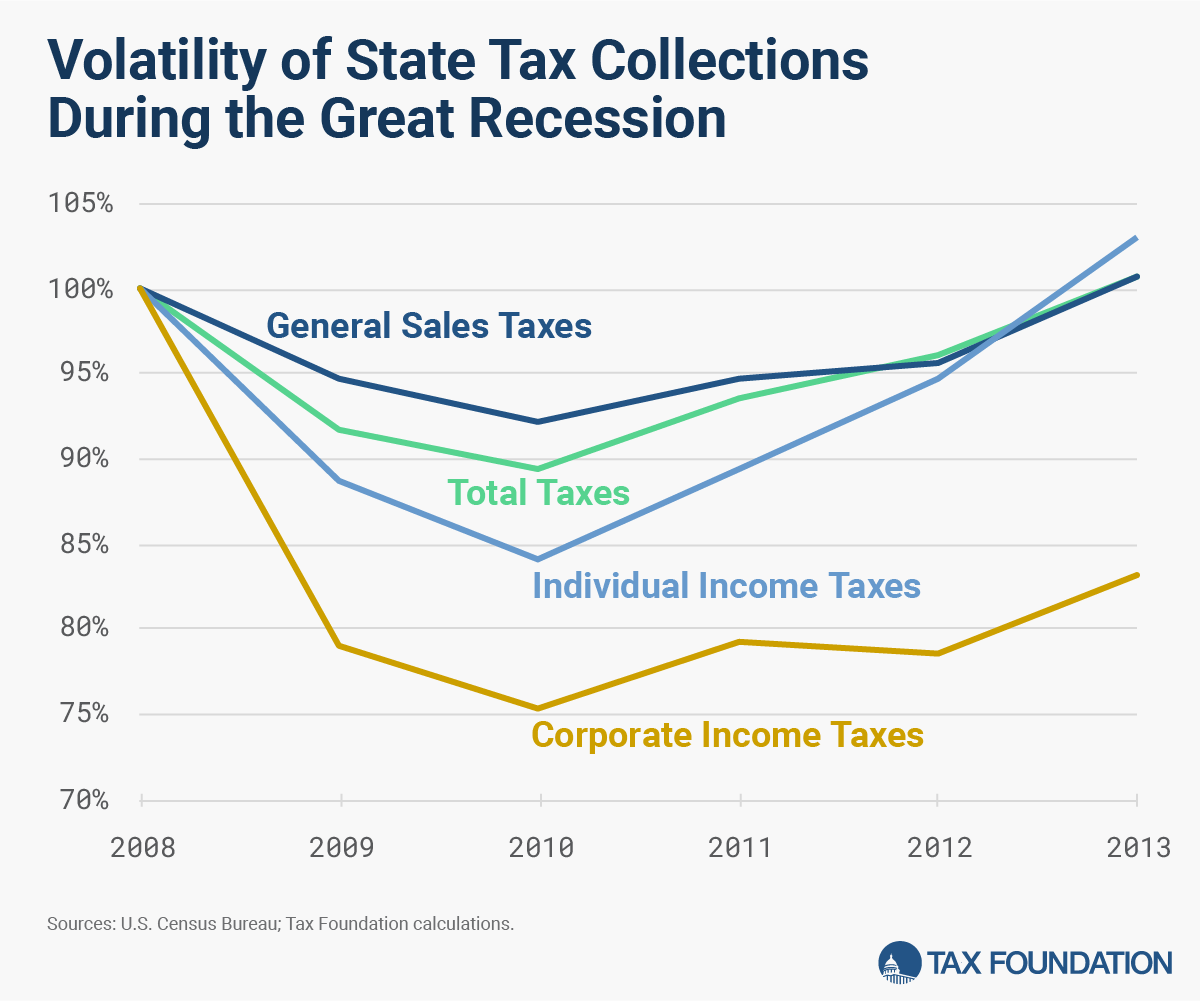

One further feature of the sales tax is its stability compared to many other revenue sources—particularly income taxes, which exhibit far greater volatility. During a recessionA recession is a significant and sustained decline in the economy. Typically, a recession lasts longer than six months, but recovery from a recession can take a few years.

, wage, salary, and investment income decline, but consumption is less affected, both out of necessity and due to the benefit of (mostly untaxable) governmental assistance, providing a smoothing effect. Income that is potentially taxable, however, falls sharply.

This phenomenon can be seen clearly during the Great Recession, when incomes fell sharply, with a concomitant decline in income taxes, but sales taxes experienced considerably less of a decline. More recently, neither income nor sales tax revenues suffered during the coronavirus pandemic due to the intensity of federal government-driven financial intervention, but in an “ordinary” recession where incomes decline, sales taxes would prove a more stable source of revenue yet again.

Defining the Potential Consumption Base

It is one thing to say that economists and public finance scholars broadly agree that an ideal sales tax base would include most or all personal consumption, while excluding intermediate transactions (business inputs). It is another thing altogether to put this knowledge into practice.

In the real world, state sales taxes in the United States fall well short of this goal, and are markedly worse at it than consumption taxes in most other countries.[20] Of the $444.5 billion that states raised in sales tax revenue in 2022,[21] an estimated $185.4 billion came from business inputs, leaving $259.1 billion generated from personal consumption—far less than would be generated if the base extended to all personal consumption transactions.

Unfortunately, defining the potential base of personal consumption is not straightforward, and sometimes policymakers have erred by simply using a measure known as personal consumption expenditures (PCE) as if it represents potentially taxable personal consumption.[22]

This measure, however, includes consumption that does not involve a transaction—including, crucially, what is known as “imputed rental” of housing, essentially the value of living in one’s home. This involves no transaction and could not be subject to sales tax.[23] On occasion, policymakers have missed this in estimating the revenue available to them with sales tax base broadening. This was one of several critical errors made in calculations for the so-called EPIC proposal in Nebraska, which sought to replace virtually all of Nebraska’s existing state taxes with one putatively broad-based consumption tax.[24]

The PCE measure also includes consumption that at least potentially involves a transaction, but which is legally beyond states’ reach. For instance, while a state could theoretically choose to broadly tax health care services, the sales tax is not permitted to extend to federal Medicare and Medicaid expenditures. And while states can, and some states do, tax groceries, they cannot tax groceries purchased using federal benefits like the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) or the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC). Internet access is likewise excluded from state taxation by federal law.

Accordingly, while 2022 saw $17.5 trillion in personal consumption expenditures nationwide, only an estimated $13.3 trillion of those involved a transaction, and, after accounting for federal law restrictions, the broadest possible personal consumption sales tax base was $11.1 trillion. If all health care and education expenditures are excluded (there are valid economic arguments for taxing both, but politically this has tended to be a non-starter), then the remaining potential base runs $10.1 trillion.

But while $10.1 trillion is significantly lower than the headline $17.5 trillion PCE figure, it remains dramatically larger than the base of personal consumption actually included in states’ 2022 sales tax bases, which we estimate at $5.2 trillion.

If states broadened their sales tax base to include all legally taxable transactions except those in the health care, education, and grocery categories, the weighted average state-level sales tax rate could drop from a current 6.01 percent to 3.99 percent. Alternatively, if bases were broadened under current rates, states would generate an additional $225 billion in revenue. If groceries were added to the base, the revenue-neutral rate would be 3.63 percent, or, alternatively, an additional $290 billion in revenue.[25]

The Basic Case for Excluding Business Inputs

Excluding business inputs gives rise to an obvious objection of favoring businesses over consumers. This, however, is a misconception, based on a misunderstanding of the very nature of the sales tax, which is intended as a tax on consumption. The upshot of taxing business inputs is not to shift tax burdens away from consumers and onto businesses, but rather to create a tax base that is dramatically broader than actual consumption—in other words, to tax final consumption (or at least some share of it) multiple times over.

This is why it can be helpful to conceptualize these purchases not just as business inputs, which they are, but as intermediate transactions, which is equally true. Taxing inputs means taxing the constituent elements of consumption, sometimes in Russian nesting doll fashion, before taxing the final good yet again.

Consequently, taxing business inputs results in nonneutral effective tax rates on consumers and disguises the true costs of government, while also, in many cases, increasing the costs of production and putting states with greater taxation of business inputs at a competitive disadvantage in attracting and retaining businesses.

When intermediate goods or services are included in the sales tax base, this may influence the choice of production method. For example, a firm might decide to purchase a cheaper but less effective technology or product, hindering efficiency and productivity, or avoid the taxable transaction altogether, favoring labor-intensive production methods over capital-intensive ones. As a result, rates of investment decline, negatively affecting future economic growth. Firms that are large or profitable enough to do so may choose to bring the production of otherwise taxable services and goods in-house to avoid exposure to a taxable transaction, which is known as vertical integration and can create its own inefficiencies if the choice would not be prudent except to reduce tax liability. Worse still, smaller or less profitable firms usually have far less capability to vertically integrate to avoid such taxes.

On the consumer side, when business inputs are included in the base, the sales tax essentially stops being a single-stage tax. When a tax applies at multiple stages of the production process as well as at the final point of sale, this results in an effective tax rate (what the final consumer actually pays in taxes in proportion to the pre-tax price of a given good or service) that significantly exceeds the statutory sales tax rate, a phenomenon known as tax pyramiding. As a result, taxing business inputs leads to nonneutral tax burdens for consumers due to the application of non-uniform effective tax rates across different categories of goods and services.

When tax is imposed on the transaction price at most or all levels of production, it is typically called a gross receipts taxA gross receipts tax, also known as a turnover tax, is applied to a company’s gross sales, without deductions for a firm’s business expenses, like costs of goods sold and compensation. Unlike a sales tax, a gross receipts tax is assessed on businesses and apply to business-to-business transactions in addition to final consumer purchases, leading to tax pyramiding.

. Few states still impose gross receipts taxes, but the typical state’s sales tax is far from a pure tax on final sales, with US sales taxes largely existing on a continuum between an ideal sales tax and a true gross receipts tax.

Significantly, tax pyramiding is likely to be regressive, as it is concentrated in goods and services consumed disproportionately (as a percentage of income) by lower-income households. The literature on this question is somewhat limited, but one older study found that effective sales tax rates on items like apparel, furniture, appliances, and alcohol were two percentage points higher than the statutory rate, and even groceries, when statutorily exempt, bore an effective rate of 2.3 percent due to pyramiding.[26]

In addition to its more concrete harms, tax pyramiding disguises the true costs of government. Final consumers, when buying goods at retail, only see the statutory rate reflected on their receipt and not the sales taxes applied and collected during the production process that get passed along to them in the form of higher prices. The degree of double taxationDouble taxation is when taxes are paid twice on the same dollar of income, regardless of whether that’s corporate or individual income.

will vary greatly across different goods and services without regard to value, profits, or price level, creating further distortions.

Unsurprisingly, scholars have found that removing business inputs from the sales tax base would promote economic growth even if the sales tax rate increases commensurately to maintain revenue neutrality. Research shows that even a partial rollback of business input taxation, offset by higher rates on the remaining sales tax base, would be highly capital- and growth-enhancing because it would lead to an increase in physical capital stock and gross state product that would more than offset the reductions in physical capital stock and gross state product attributable to a commensurate increase in the sales tax rate.[27]

How Business Input Taxation Turns the Sales Tax into a Production Tax

It is widely recognized that taxing business inputs leads to tax pyramiding. Less commonly understood is how it transforms the sales tax from a tax on consumption to, at least in part, a tax on capital investment.[28] It takes a tax that is neutral with regard to in-state investment and turns it into a discriminatory tax on a state’s own businesses, disproportionately affecting smaller firms with less capacity to vertically integrate services.

Even when a sales tax is destination-sourced (meaning it is imposed where the product is purchased or used, rather than at the location of the producer or seller), as is almost invariably the case, and when the base is limited to final consumer transactions (which, unfortunately, tends not to be the case), the rate in a particular jurisdiction can induce cross-border shopping. While cross-border shopping can be detrimental to in-state, brick-and-mortar retailers that lose business to retailers in other states, it does not otherwise impede a business’s ability to compete with out-of-state competitors, since out-of-state customers are taxed at their own local rate, or are legally required to remit use taxes at their own local rate, not at the rate in the business’s jurisdiction.[29] As soon as taxes are imposed on a business’s own purchases, however, businesses in that jurisdiction are placed at a disadvantage against competitors not subject to such taxes in their own states. These taxes represent an additional cost of production that is not borne by their competitors based elsewhere, even if they sell into the same markets.

The consequence is that a putative tax on consumption is transformed into a production tax. Prior analysis has shown that the taxation of business inputs imposes a penalty on saving and investment that is akin to corporate income taxes,[30] but in some ways, the sales tax on business inputs is likely to be more harmful for states, since corporate income taxes are mostly apportioned based on sales (not the place of production), whereas a tax on business inputs makes the taxing state less competitive as a location for business activity.

Depending on the market for a given product, the result of taxes on business inputs is either to (1) increase consumer prices or (2) reduce the profitability of the taxed business activity—or both. Estimates vary, in the latter case, on how much of the cost will be borne by labor in the form of lower wages and by capital in the form of lower investment returns, though both effects are real and of importance to public policy.[31] Firms in states that tax an inordinate amount of business inputs are at a disadvantage with out-of-state competitors.

It is mostly correct to state that tax pyramiding means that the tax is embedded in the final price several times over. Tax represents a disproportionate amount of the final price of the good because it is imposed at multiple levels of production.[32] But whether, and how much, this raises the final price of the product—rather than cutting into profitability, reducing wages, or eliminating the production activity entirely or moving it across state lines—will depend on whether regionality is integral to the product.

Milk, for instance, is almost always sourced within a few hundred miles of the grocery stores in which it is sold to consumers, due to the costs of transporting it and the rate of spoilage, whereas cereal crops can be sourced from and processed anywhere in the country, and it is often cheaper to ship produce across oceans than across a few hundred miles of road. If multiple layers of sales tax were imposed on the dairy industry by applying the tax to milking machines, the services of milk processing plants, and the services of milk distributors, then most of the additional tax would likely be borne by consumers, as milk from Iowa is not a competitive economic substitute for milk from California for a family living in Los Angeles.[33]

If, however, a state were to levy multiple layers of tax on the processing of grains into breakfast cereal or granola, then over the long run, we might expect the tax to be borne in greater proportion by producers (both investors and employees), because these producers sell in a competitive national marketplace with other enterprises that are not similarly taxed. Either they will be forced to accept lower wages and lower investment returns (which may affect future business decisions), they will move some of their operations to another state (which has economic costs), or they will find themselves increasingly boxed out of the market by firms located elsewhere, which will take over their market share.

When the effects of pyramiding are absorbed by businesses, moreover, the impact is far from uniform—and the most economically rational response may be to adjust business decisions in ways that would otherwise be inefficient. For instance, a company may choose to vertically integrate more of its processes, bringing the production of machinery or component parts in-house, or building out its own distribution operations, even if it might otherwise be more efficient to contract with other firms with greater expertise and economies of scale in these areas, all to avoid the additional layer of tax imposed if these activities constitute a taxable transaction rather than an internal process.

Alternatively, businesses may move some or all of their operations to states with better treatment of costly inputs. This can mean physically relocating a facility, but it might also mean expanding elsewhere, or purchasing from suppliers that have more consolidated processes or operate in states where their intermediate transactions are untaxed.

And businesses lacking the capacity to make these adjustments—particularly smaller operations—can find themselves at a competitive disadvantage. A small business can be very good at one particular thing and may choose to outsource many processes that are not at the core of what it does. But its larger rivals, which may be better positioned to vertically integrate (or may have already found it economically advantageous to do so independent of sales tax considerations), receive more favorable tax treatment.

Finally, pyramiding causes consumption taxes to discriminate across not only firms but also industries and types of products. It favors some manufacturing processes over others, regardless of whether those processes are consistent with other goals (durability, aesthetics, sustainability, local market conditions, etc.), and it favors kinds of products that either have shorter production chains or have intermediate transactions that are better shielded from sales taxation. This shifts both investor and consumer behavior toward inferior options: inferior as a matter of revealed preference, since consumers and investors favored another option until tax differentials nudged them in a different direction.

This is not what a consumption tax is for, and it works to the detriment of producers, consumers, and the overall competitiveness of states imposing these taxes. States must raise tax revenue, and all taxes affect economic behavior at some level, but the goal should be to interfere with the market as little as possible. Occasionally, states may wish to promote specific goals, but it is doubtful that policymakers taxing business inputs believe that anyone is better off if the tax code influences the size of businesses, or how specialized they are. And certainly, no state legislator ever thinks that the tax code would be better if only it encouraged jobs and production to take place in other states, or if it put in-state businesses at a disadvantage against regional or national rivals, or if it drove up consumer costs in highly nonneutral ways. Yet this is what the sales tax does whenever it is levied on business inputs.

Research shows that taxing business inputs does precisely what economists would predict. One study described earlier finds that if states were able to reduce their taxation of business inputs by even 25 percent—that is, to go from about 41.7 percent of their base falling on intermediate transactions to about 31.3 percent [34]—while making up the revenue with a commensurately higher rate applied to the rest of the sales tax base, they would boost capital accumulation (the amount of machinery, equipment, and overall capital investment in the state) by 1.2 percent and increase gross state product by 0.4 percent.[35] Nationwide, that would represent an additional $115 billion a year in economic output.

These findings should be compelling enough, but they substantially understate the economic benefit because they are only focused on the direct effects of reducing the tax burden on production. The calculation is based on what is known as a closed system, which assumes no competition and no ability to shift activity—production or consumption—to other states.

In reality, states that do a better job of exempting business inputs not only increase the productivity of their own firms but also make themselves more attractive for investment compared to their peers and give in-state companies an edge against out-of-state competition faced with additional levels of taxation. Conversely, states that expand to new categories of business inputs make themselves less attractive for affected businesses that may otherwise wish to operate in the state and make it harder for in-state firms to compete with their less-taxed interstate rivals.

Defining Business Inputs

The broad theoretical agreement that an ideal sales tax base would exclude business inputs tends to break down on the seemingly simple question of what constitutes a business input. Imagine, for instance, a company manufacturing kitchen utensils. Which of these business purchases constitute business inputs that should, ideally, be exempt from taxation?

- The metal and other raw materials used in the utensils themselves

- The machinery and equipment used to cast, mold, or cut the utensils

- The electricity and fuel used to power that machinery

- The packaging for the utensils

- The contract for shipping and distributing the utensils

- The marketing contracts to advertise the products

- The legal, accounting, and other services necessary to operate the business

- The landscaping and janitorial services for plants, warehouses, and corporate offices

- The electronics and furnishings in the corporate office

- The subscription for a sales database

- The cloud services and data processing used for manufacturing, distribution, and logistics

- The purchase of their utensils by a home goods store for resale to consumers

Nearly everyone would agree that the raw materials and the sale for resale should be exempt, and states are largely uniform in exempting these transactions. States are more inconsistent in exempting machinery and equipment and business fuels, and sometimes only do so for select businesses or industries through targeted incentives. Increasingly, data services—cloud storage, data processing, client databases, software (including software as a service), and machine learning—are subject to tax, as are many goods “consumed” by businesses that are not a component of the final product.

Because most services have historically been exempt from sales taxation, legal, accounting, human resources, advertising, and similar services are frequently exempt, but proposals to expand to services, or to a broad array of digital products, could imperil this treatment and capture a wide new range of intermediate transactions. Few states have a consistent approach to the tax treatment of business inputs, and it is often difficult to identify any governing philosophy.

Across the country, some defenders of the status quo often endorse a narrow definition of business inputs, focused largely on physical identities. Distinctions are often made between goods and services consumed “by” the business rather than embedded in the final consumer product, or between things that are “integral” rather than ancillary to production. A set of kitchen knives contains the metal and other raw materials used in its manufacturing but does not contain the machinery that made it, nor the fuels that powered them. And whereas the machinery and fuels are necessary for the creation of the final product, strictly speaking, the marketing budget, the shipping contract, the legal team on retainer, and the contracted services that keep the manufacturer’s office up and running are not. This lends itself to the drawing of several possible lines in defining business inputs for exemption purposes:

- Just the raw materials and the sale for resale, to avoid double taxing the actual components of the product

- Everything directly used for or consumed in production, like machinery and equipment (which depreciates and is ultimately consumed by the production process) and fuels, in addition to raw materials and sale for resale

- Virtually everything purchased by a business as part of its business activity, with narrow exceptions for purchases that function as final consumption

Lawmakers sometimes balk at the third definition, as it is the most expansive. It may also come across as too simple, as if it elides the hard work of providing a more robust definition. Yet it is, in fact, the most appropriate definition of business inputs, because it conforms to the economic realities of business purchases, and the exemption of these purchases aligns the sales tax with its intended function as a tax on consumer purchases.

This becomes apparent both by interrogating the rationale for business purchases regardless of category as well as through an appreciation of the purpose of business input exemptions.

With limited exceptions, businesses make purchases in service of their bottom line. This does not guarantee that their transactions are prudent or turn a profit: businesses make poor investments all the time and are punished by the markets when they do so. But a business purchases advertising time, cloud computing, packaging products, shipping contracts, and facility maintenance services for the same reason it purchases raw materials. They are all means to the end of the (hopefully) profitable production and sale of some valuable good or service. Not all of these purchases will be resold or physically embedded in final products, but they are only purchased because they are part of the business model, and thus part of the economic identity of their product.[36]

The purposes of a business input exemption, moreover, are consistent with a broad definition. Those purposes, simply stated, are to:

- Tax final consumption uniformly, avoiding tax pyramiding where a final product is taxed on its value several times over, and where some products are taxed more aggressively than others

- Avoid distorting economic decisions on capital investment, location, vertical integration, or production processes

- Prevent the sales tax from disadvantaging in-state production or putting particular (often smaller) companies at a competitive disadvantage

The nature of the business input subject to tax can affect the intensity of the distortion—some inputs pyramid more than others—but all are, by definition, distortionary.

Navigating the Digital Frontier

Our world has changed. Many formerly tangible products have been replaced by digital cousins: we download e-books, stream movies and music, store photographs in the cloud, and subscribe to services for our homes, cars, and even appliances. These are all forms of consumption, and it is reasonable for sales taxes to reflect this new reality, particularly where a digital product has taken the place of tangible property that is subject to tax.[37]

Personal consumption of digital products, however, is dwarfed by the business applications, and most proposals to include digital products in the sales tax base would represent a vast expansion of business input taxation. The real money is not in Spotify accounts or Netflix subscriptions, but in digital controls, commercial cloud computing, inventory management, automated production lines, digital payments, machine learning, software (and platform and infrastructure) as a service, digital advertising, and data processing.

During the pandemic, the Multistate Tax Commission (MTC) began working on definitions of digital products for states to consider for the purposes of their own sales taxes. The Commission has taken pains to insist that they are merely seeking to define what constitutes a digital product, without taking a position on which digital products (if any) should be taxable, but there is a risk that policymakers will incorporate a broad definition into their sales tax base. That would be an egregious policy mistake.

An outline published by MTC offers extensive digital product exemplars within a variety of industries. Agriculture, manufacturing, health care, construction, education, energy, food, retail, office products, telecom and information technology, and travel all make the list. Examples of digital products in the agricultural industry include, just to cite a few examples, digital pasture management, digital seed technology, drones, farm management software, GPS guidance systems, machine learning (used to improve crops and identify pests), monitoring technology, robotic harvesting, sensors, smart irrigation, and data and artificial intelligence for assessing things like soil quality and plant yield.

Sometimes it can be difficult to categorize a particular good or service as a business input or a consumer transaction without knowing the identity of the purchaser, because businesses and individuals alike purchase some of the same products. It is not, however, terribly difficult to recognize that digital seed technology has limited consumer applicability, and that hobbyist gardeners are not using robotic harvesting or operating combines with GPS guidance systems.

Agriculture, moreover, has generally been treated fairly well by state sales taxes, with exemption certificates often eliminating the taxability of many of the intermediate transactions that are not definitionally excluded from the base. Were digital products broadly taxed, that would change overnight.

For manufacturing, digital goods could include modeling, simulations, automated production lines, data storage and processing, digital controls and machines, robots, software as a service, and digital advertising, along with categories also applicable to agriculture, like machine learning. The health-care industry’s digital products are ample, too, and might include storage of medical records, wearable devices, artificial intelligence and augmented reality used in medicine, cloud computing, robot-assisted surgery, virtual biopsies, and much more.

Notably, these are not just areas where most states exempt business inputs because they do not tax most digital products. Rather, they are areas where lawmakers have, through concerted efforts over years and decades, sought to limit the scope of sales taxation. An insufficiently cautious expansion of the base to digital products could indiscriminately wipe out the conscious policy choices of legislatures going back decades.

The digital world, meanwhile, is inherently more mobile than the production of tangible goods. If a state taxes intermediate digital transactions, businesses will adapt by moving as many of those processes as possible out-of-state, depriving the taxing state of economic activity (and tax revenue) it would have otherwise enjoyed. And taxing digital products is not just—or even primarily—about taxing the tech industry. As the exemplars above suggest, virtually all companies rely on digital products to do business. Applying the sales tax to digital products would impose additional layers of tax on virtually every business in the Commonwealth.

The broad reach of digital products taxation is an important reason to reject the taxation of digital business inputs on equity grounds as well. It is occasionally argued that, while business inputs would not be taxed under an ideal tax system, the fact that many intermediate transactions involving tangible goods are already taxed makes it necessary to impose similar burdens on digital intermediate transactions for the sake of fairness. Even setting aside the question of whether new economically damaging policies should be adopted to parallel existing flaws, and neglecting the differences in relative scope (taxing most or all digital business inputs because a subset of tangible ones are taxed), it is a mistake to see physical and digital products as occupying independent spaces. Every business consumes digital products, even if it sells tangible goods.

Approaches to Exempting Business Inputs

Business inputs currently included in the base, or potentially included based on new categorical expansions of the tax base, can be exempted in one of two ways: based on the nature of the product or the identity of the purchaser. Either approach can suffice, or they can be used in tandem.

Most states exempt manufacturing machinery from their sales taxes, since such machinery is clearly part of the production process and its consumption is almost exclusively by businesses. (Very few of us acquire sheet metal bending machines for personal use.) The same approach works for a variety of business services, like marketing, engineering, logistics management, and human resources, which are almost exclusively the province of businesses. For such categories, it is administratively simplest to grant an outright exemption.

Some professional services, however, can be consumed by both businesses and individuals. For instance, a consumer might retain the services of an accountant or a tax preparer, and a business might also contract with an accountant. Many tangible goods can be purchased by both businesses and individuals as well—desk chairs, for instance.

In such cases, an exemption could be granted based on the identity of the purchaser. Many states already have experience with this approach, exempting any purchase by a nonprofit entity and select purchases by farms and certain types of businesses, based on the identity of the purchaser. It would be relatively easy to extend these provisions to businesses more broadly to apply to the purchase of certain professional services, or to any other goods and services that are commonly purchased both for personal and business use.

If, however, a sales tax fails to distinguish the ultimate purchaser for goods that are consumed by the business rather than used in the course of production and sale (equipment, machinery, raw materials, packaging, advertising, etc.),[38] the consequent tax pyramiding may be less extreme than with the inclusion of more direct production inputs. The problem still exists, and should be avoided wherever possible, but the resulting pyramiding is at least less dire.

Under an ideal sales tax, exemptions based on the identity of the purchaser could do away with the entire patchwork quilt of business input exemptions. Anything in the sales tax base would be taxable if purchased by a final consumer and exempt if purchased by a business. That said, applying this broadly would wipe out all inputs currently included in the sales tax base—good policy, to be sure, but a significant hit to state revenue.

It is, however, a responsible way to approach expansion of the sales tax base into new areas, like digital products. Iowa, for instance, adopted a commercial enterprise exemption that exempts business purchasers from sales tax on purchases of specified digital products, prewritten computer software, data storage, information services, software as a service (SaaS), and certain other digital services, provided the products are purchased and exclusively used by a commercial enterprise.[39]

A policy of regularly reviewing and reducing reliance on the taxation of business inputs is important as well, and can be paired with other reforms.

Reconsidering Existing Consumption Exemptions

Most states impose their sales taxes on bases that consist of many goods—with economically significant policy carveouts—and relatively few services. Historically, most state sales taxes have been imposed on transactions involving tangible property: appliances but not apps, light fixtures but not landscaping. This was less a conscious choice than an accident of history, a relic of the fact that so many sales taxes were first imposed during the Great Depression, when services comprised a far smaller share of the economy. Back then, it was administratively simpler to focus almost exclusively on later retail sales. Subsequently, even more recently adopted sales taxes have often been modeled on sales taxes of an earlier origin.

Exemptions for Services

Fortunately for the nation’s economy but unfortunately for the reliability of state sales taxes, today’s economy has little in common with that of the 1930s or even the 1990s. Higher incomes and changing consumer tastes have shifted a greater share of consumption to services, while a digital economy is upending traditional categories.

We subscribe to streaming services rather than buying DVDs, VHS tapes, CDs, or records (all of which were taxable); we purchase e-books (sometimes untaxed) rather than paperbacks (invariably taxable); we obtain programs and games through digital downloads rather than physical media (disks or cartridges). Increasingly, younger generations purchase “experiences” more than tangible goods—and most of those experiences involve services, whether it’s fitness classes or cooking lessons or excursions.

But it’s not just new services; it’s also a matter of older services taking on greater importance in the modern economy. Domestic help has all but vanished, but increasingly, there’s an app for that, or at least a number to call: house cleaning services, dog walking and pet sitting, ridesharing as an alternative to car ownership, or landscaping services in lieu of buying a lawn mower, to name just a few. The mower was taxed; its replacement (the lawn care service) is not. It is a story that can be told many times over. It is the story of a sales tax code built around an economy that no longer exists.

Slowly and fitfully, states are modernizing their tax codes, with the greatest progress coming in areas of nearly one-for-one replacements: streaming services, e-books, and select other digital goods that are clear substitutes for already-taxable tangible goods. Other personal services remain outside sales tax bases in most states, even as consumption patterns shift.

The resulting base erosion is undesirable along three axes: stability, economic efficiency, and equity. Base erosion undercuts state revenues and, to the extent that it shifts the balance of the tax system toward other, more distortionary revenue streams (particularly income taxes), can reduce overall economic competitiveness.

At the same time, broadly exempting services is regressive. Consumption of personal services tends to be more discretionary than consumption of goods. Consequently, higher-income individuals tend to spend a greater share of income on services, which are frequently untaxed. Expanding the sales tax base to additional services rights an accidental wrong in the sales tax as currently formulated, one that presently favors wealthier individuals.

In broad terms, services can be conceptualized as falling into five categories:

- Business services (e.g., advertising, employment services, consulting, and public relations)

- Personal services (e.g., dry cleaning, fitness classes, haircuts, lawn care, and personal storage)

- Professional services (e.g., legal, accounting, medical, engineering, and other services generally associated with specific licensing or educational requirements)

- Services to real property (e.g., repairs, maintenance, construction, and installation of fixtures)

- Services to tangible personal property (e.g., delivery, installation, and repairs of furnishings and appliances)

In a well-structured sales tax, business services would be exempt, but all other categories could be taxable, though in some cases—particularly professional services—with exemptions for intermediate purchasers. These exemptions can be provided for using broad industry categories (e.g., exempting engineering as predominantly a business-to-business transaction), based on the purchaser being a business, or some combination of the two.

Policymakers can and should explore ways to tax consumer services that are currently exempt. Potential examples include automobile maintenance and repair services, home appliance installation, personal storage services, utility services, barber shops and salon services, dating services, guided tours, cleaning and upholstery services, counseling services, gym and health club memberships, dry cleaning, tax return preparation, personal instruction (e.g., tennis lessons, dance lessons), personal cloud hosting services, streaming audio and video services, car washes, amusements, landscaping, and event admissions, to name a few.

Including these and other consumer services is a good start in right-sizing the sales tax and addressing ongoing base erosion, but such inclusions are not a silver bullet. Policymakers are often led to believe that taxing services will unleash a torrent of new revenue, only to find that the real money is in business-to-business services (which should not be taxed), not haircuts.

Exemptions for Goods

Goods are declining as a share of taxable consumption as the US evolves into an increasingly service-oriented economy, but they still constitute 33 percent of all personal consumption, while potentially taxable goods (those involving a transaction and where taxation is not restricted by federal law) comprise 51 of legally taxable retail transactions and 57 percent of non-health care and education taxable consumption.[40]

Moreover, restaurants account for a sizeable share of services, even though restaurant meals are often colloquially understood as goods—and they are one of the few services already universally taxed by states with a sales tax. While the categorization of a restaurant meal as a service is correct, it may be instructive to briefly imagine all purchased food, from whatever source, as goods. In that case, 70 percent of taxable consumption would constitute goods.

Policymakers run headlong into this reality when they seek to tax more services as a revenue-raiser, or as a revenue offset for tax reductions elsewhere. This counsels a degree of modesty in what base broadening can accomplish, but may also suggest a hard look at existing exemptions for tangible goods.

Groceries, clothing, medication, utilities, and gasoline are among the most common economically significant carveouts from states’ sales tax bases, often justified on the grounds that they are necessities or that taxing them makes the sales tax more regressive. Those reasons are worth taking seriously, but there are good reasons—even for the most progressive legislators—to reconsider whether their states’ sales tax treatment of these goods is achieving their intended policy objectives.

The conventional wisdom overstates the degree to which sales taxes are regressive, with economic research demonstrating that over a lifetime, the sales tax is much closer to distributionally neutral than is commonly believed, and that a fair amount of the regressivity that remains is the product of state tinkering with sales tax bases.[41]

Low-income individuals consume a greater share of their income than higher earners, who have a greater capacity for saving, so sales taxes apply to a higher share of low earners’ income. This pattern substantially dissipates over time, however, because people earn in order to spend, and saving today is simply deferred spending. Over a lifetime, cumulative income and cumulative spending largely converge, even if spending is higher at different stages of life.

Moreover, income levels are not necessarily a good measure of ability to pay. A superficially surprising but well-known quirk in large consumer datasets is that the households that own the most cars are concentrated in the highest and lowest income strata. This is not, of course, because cash-strapped households somehow find a way to stockpile vehicles. Rather, it’s because a working mom earning minimum wage, a full-time medical student from a wealthy family, a fixed income retiree, and a wealthy couple spending down their retirement nest egg all show up in the data as having low income streams, even though their economic conditions vary wildly.

Some of these differences will endure throughout a lifetime, and others are simply stages of life. Most people start out with modest incomes and consume the majority of it, then advance in their careers and save a greater proportion of income, and then retire and begin spending it down. Within a single person’s lifetime, sales tax liability as a share of income will resemble a bell curve, reflecting different stages of life more than differences across people.

Of course, this does not render the distributional differences irrelevant. Some people live on limited incomes their entire lives, and even those who are only temporarily resource-constrained will have less capacity, at that stage, to bear additional costs. But understanding the way sales taxes apply across a lifetime should at least temper the view that broadly taxing consumption—including essential goods—is objectionably regressive. The wider lens permits an evaluation of the trade-offs between greater progressivity, on the one hand, and the revenue stability and comparatively pro-growth profile of sales taxation compared to other potential revenue streams.

More to the point, some efforts to combat regressivity fail to do so, sacrificing the benefits of a broad sales tax base without providing a benefit to lower-income households. Virtually any exemption, of course, will be poorly calibrated: even if clothing represents a greater share of consumption for low-income households, for instance, most of the foregone revenue from a clothing exemption will benefit middle- and higher-income households, which spend far more on clothing (and on most things) in nominal terms.

Some exemptions, moreover, are particularly ill-considered, the grocery exemption foremost among them. Perhaps counterintuitively, if states are inclined to forgo a given amount of sales tax revenue, a sales tax rate reduction benefits lower-income households more than a grocery exemption. At the lowest decile, our research finds that households experience nine percent more sales tax liability under a sales tax with a grocery exemption than one with groceries in the base, assuming that rates are adjusted to generate the same amount of revenue from each tax base.[42]

It is easy to construct the basic narrative by which policymakers have assumed that a grocery tax exemptionA tax exemption excludes certain income, revenue, or even taxpayers from tax altogether. For example, nonprofits that fulfill certain requirements are granted tax-exempt status by the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), preventing them from having to pay income tax.

is highly progressive. As previously observed, lower-income earners, by necessity, consume a greater share of their income, and thus their sales tax liability is higher as a percentage of personal income. This is particularly salient with groceries, both because they are a necessity of life and because demand for groceries cannot fully scale with income. Try as he might, a billionaire cannot consume orders of magnitude more groceries than a minimum wage employee. Consequently, the logic runs, exempting groceries disproportionately benefits lower-income earners by reducing their taxable consumption by a greater share than it is reduced for higher earners.

This narrative, however superficially compelling, is marred by several flaws. Most importantly, it either neglects or fails to appreciate the full impact of the universal policy of exempting from sales tax any purchases made using federal food-purchasing assistance programs, primarily the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), but also the more narrowly targeted Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC). States’ receipt of federal grants to administer these Food and Nutrition Service-funded benefits is contingent upon exempting these purchases from sales tax, and all states do so—even if groceries are otherwise in the sales tax base. This policy alone dramatically reduces taxable consumption for the lowest income deciles.

Additionally, the conventional wisdom underestimates the degree to which higher consumption of groceries does scale with income. Higher earning households purchase not only more, but higher qualities of, groceries. Low-income households, in fact, are more likely to purchase taxable substitutes to what states classify as groceries, a category that traditionally only covers unprepared foods. For lower-income working families, prepared foods—rotisserie chickens, deli items, fast food, and more—are often more economically efficient than buying raw ingredients and making home-cooked meals, but prepared foods are taxed, whereas ingredients are exempt when states adopt a grocery tax exemption. The result is that a household in the fifth decile spends almost 70 percent more than a household in the first decile, and a household in the top decile spends over three times as much as a household in the lowest.

Finally, while low-income households spend more on groceries as a share of income than the highest-income households, they do not necessarily spend more on groceries relative to other necessities. Compositional effects matter. If lower-income families spend moderately more on groceries as a share of income but substantially more on other household goods, then they will be worse off under a tax code that exempts groceries but with a higher rate than would be necessary were groceries included in the base. Given not only substitution effects—prepared foods for unprepared—but also, crucially, the exemption of SNAP and WIC purchases for many low-income households, this is not just a hypothetical but the reality for many families.

These programs do not, of course, cover all grocery purchases by low-income households. The crucial point is that they cover a substantial portion of them, whereas these households typically bear the full burden of the cost of other goods subject to sales tax, so the benefit of rate relief is greater than the benefit of exempting a category of goods for which they already enjoy a partial, but highly targeted, exemption.

The result is that a policy designed to inject progressivity into the sales tax has the opposite effect, increasing tax liability on the lowest-income households, with most savings concentrated on middle-income households that can be best helped in other ways. And once it becomes apparent that the grocery tax exemption fails to achieve its stated objective, the trade-offs associated with the policy come into sharper relief. Grocery purchases are a sizable and stable share of personal consumption and exempting them from consumption taxation not only erodes the sales tax base, necessitating higher rates than would otherwise be necessary, but also increases revenue volatility.

Further common exemptions include gasoline and household utilities, often justified as an attempt to avoid double taxation. This too is an argument worth addressing.

The Interaction of Sales and Excise Taxes

Whereas the general sales tax is intended as a broad tax on consumption, certain products are also subject to excise taxes, sometimes termed “special sales taxes,” raising the question of whether it is appropriate to include these products in the general sales tax base as well.

Alcohol and tobacco are almost invariably subject to sales tax despite also being exposed to product-specific excise taxes, whereas only six states subject gasoline to the sales tax, with motor fuel taxes evidently regarded as replacements for, rather than supplements to, sales taxation.[43] Insurance, which is subject to state-level premium taxes, tends to be excluded from sales tax bases, while cellular phone service, which is exposed to multiple wireless taxes, remains in the sales tax base in all but three states and the District of Columbia.[44] Residential energy, typically taxed under state utility taxes, rarely shows up in sales tax bases. States lack any real consistency on the issue.

At a conceptual level, a strong case can be made for including a product in the sales tax base even if an excise tax is also levied on its purchase or utilization. Whether this is defensible in practice depends on the rate of, and justifications for, its excise taxation.

Consider, for instance, taxes on motor fuels. Transportation is undeniably consumption, so it seems appropriate that the purchase of gasoline would be taxable, just like purchasing the vehicle itself or (in many states) automobile maintenance and repair. But driving is not just personal consumption. It also consumes public resources by putting wear and tear on roads and contributing to congestion, and it creates other negative externalities, like pollution. A well-calibrated gas taxA gas tax is commonly used to describe the variety of taxes levied on gasoline at both the federal and state levels, to provide funds for highway repair and maintenance, as well as for other government infrastructure projects. These taxes are levied in a few ways, including per-gallon excise taxes, excise taxes imposed on wholesalers, and general sales taxes that apply to the purchase of gasoline.

is essentially a user feeA user fee is a charge imposed by the government for the primary purpose of covering the cost of providing a service, directly raising funds from the people who benefit from the particular public good or service being provided. A user fee is not a tax, though some taxes may be labeled as user fees or closely resemble them.

, with drivers paying for their road usage. To the extent that this is the case, it makes sense for this tax to be in addition to the general tax on consumption. Currently, however, few states do this.

Similarly, to the extent that excise taxes on alcohol or tobacco are designed to internalize some of the negative externalities associated with their use, or to cover government costs directly attributable to them, there is a strong case for levying them on top of the existing sales tax. Sales of alcohol and tobacco require specific enforcement regimes that sales of, say, breakfast cereal, do not,[45] and their use or misuse can also give rise to costs disproportionate to those created by other goods. Similarly, utilities fall under a specific regulatory regime that must be funded. To the extent that excise taxes on such products are aligned with these costs, and revenues are earmarked for such purposes, “stacking” excise and sales taxes is not double taxation.

The case is dramatically weakened, however, when the additional excise taxes are designed primarily as a revenue-raising measure above and beyond costs associated with the product’s sale or use. This is particularly true when excise tax revenues are deposited into the general fund or designated for unrelated expenditures.

Ultimately, this yields a better case for constraining excise taxes than it does for excluding such products from the general sales tax. Nevertheless, policymakers determining whether to include a currently exempt, but excised, product from the sales tax base will inevitably have to take into account the resulting overall tax burden. In some circumstances, it may be possible—and desirable—to pair inclusion in the sales tax base with a reduction of existing excise tax rates.

Remote Sales Tax Considerations

The Supreme Court’s 2018 decision in South Dakota v. Wayfair eliminated the old physical presence standard for sales tax nexus, allowing states to require out-of-state retailers to collect and remit tax on sales to in-state customers, provided that these requirements do not unduly burden interstate commerce. (States have also adopted sets of rules for marketplace facilitators, requiring them to collect and remit tax on behalf of businesses selling on their platforms.) The Court did not expressly spell out the minimum standards necessary to avoid imposing an undue burden, but some dicta regarding the challenged South Dakota law has generally been taken as a guide to the Court’s thinking, and—even beyond bare constitutionality—helps constitute a framework for an efficient remote sales tax regime.[46]

Safe Harbors for Small Sellers

All sales taxing states have created a safe harbor for small remote sellers to avoid burdening out-of-state retailers with only minimal sales into the state.[47] These so-called de minimis exemptions reduce compliance and administrative costs and help ensure that the cost of collecting and remitting the tax will not exceed a company’s net revenue from transactions within the state. They also help insulate states from potential legal challenges, since the lack of a safe harbor—or a poorly designed one—can impose unconstitutional burdens on companies and throw a state’s entire remote sales tax regime into doubt.

Existing de minimis exemptions consider the number of transactions in a state, gross sales revenue, or both—under both “and” and “or” systems. Increasingly, states that included a transactions threshold are abandoning it in favor of a gross sales threshold, a welcome development. A well-designed safe harbor should:

- Take the size of the state’s economy into consideration, with higher de minimis thresholds in larger states

- Be denominated in gross sales, not transactions, to avoid the possibility of imposing burdens in excess of profits

- Be calculated using retail sales, or potentially taxable sales under the state’s own sales tax base

- Avoid “notch effects,” where exceeding the safe harbor imposes a retroactive obligation on already-completed transactions

A transactions threshold introduces complications that are absent from a gross sales standard. Statutes are silent on what constitutes a transaction—an order, a shipment, or an individual item—and even if guidance is provided (as is typically the case), the definition of an “item” is no easy matter, particularly if certain items constitute part of a larger whole. A dollar-denominated gross sales threshold better comports with the purpose of the safe harbor and is easier to quantify. Moreover, a small business might have more than 200 sales into a state worth $5 apiece, in which case compliance costs can easily outstrip the amount of sales tax collected and remitted, and more importantly, could exceed the company’s profits on those sales, giving rise to claims of undue burden.

States should ideally define sales volume with reference to retail sales, not all transactions. If, for instance, a business sells manufacturing machinery (generally exempt as a business input), but also has a few branded tchotchkes as retail items, it makes very little sense for hundreds of thousands of dollars of untaxed business-to-business purchases to put a company over the threshold for collecting sales tax on a few hundred dollars of taxable retail sales. Or imagine a small business that sells replacement parts to manufacturers in a tri-state area. Perhaps a very small number of consumers also own equipment for personal use, and occasionally place an order directly with this provider, which otherwise almost exclusively trades in untaxed wholesale transactions. If these untaxed wholesale transactions are enough to exceed the safe harbor, then even a single sale to a consumer is enough to require full compliance with the state’s remote sales tax regime—an outcome that makes little sense.

In a world without transaction costs, a state’s own sales tax base would be the ideal reference point, such that a transaction that is exempt from the sales tax should not count toward the gross sales threshold. In practice, however, using a threshold of retail sales is arguably superior, because it does not require a small business to learn the intricacies of a particular state’s tax code before it reaches a threshold where compliance is necessary. If a business must track pre-threshold sales against every state’s unique tax base, much of the cost of compliance will fall on businesses that lack nexus to collect and remit.

Finally, states should avoid creating “notch effects” where remote sellers are obligated to remit tax for transactions that occurred prior to attaining the state’s threshold for compliance. This is a significant issue for remote sellers, as they never collected sales tax on those transactions in the first place and have no way to go back to the purchasers and collect it now, meaning that the financial burden for sales tax on prior transactions falls on the retailer, even though the incidence of the tax is normally on the consumer. Once a business exceeds the de minimis threshold, however, all future transactions—going into future years—should be subject to collection and remittance requirements unless and until there is a future full year in which the business falls below the threshold.[48]

Embracing Unity and Uniformity

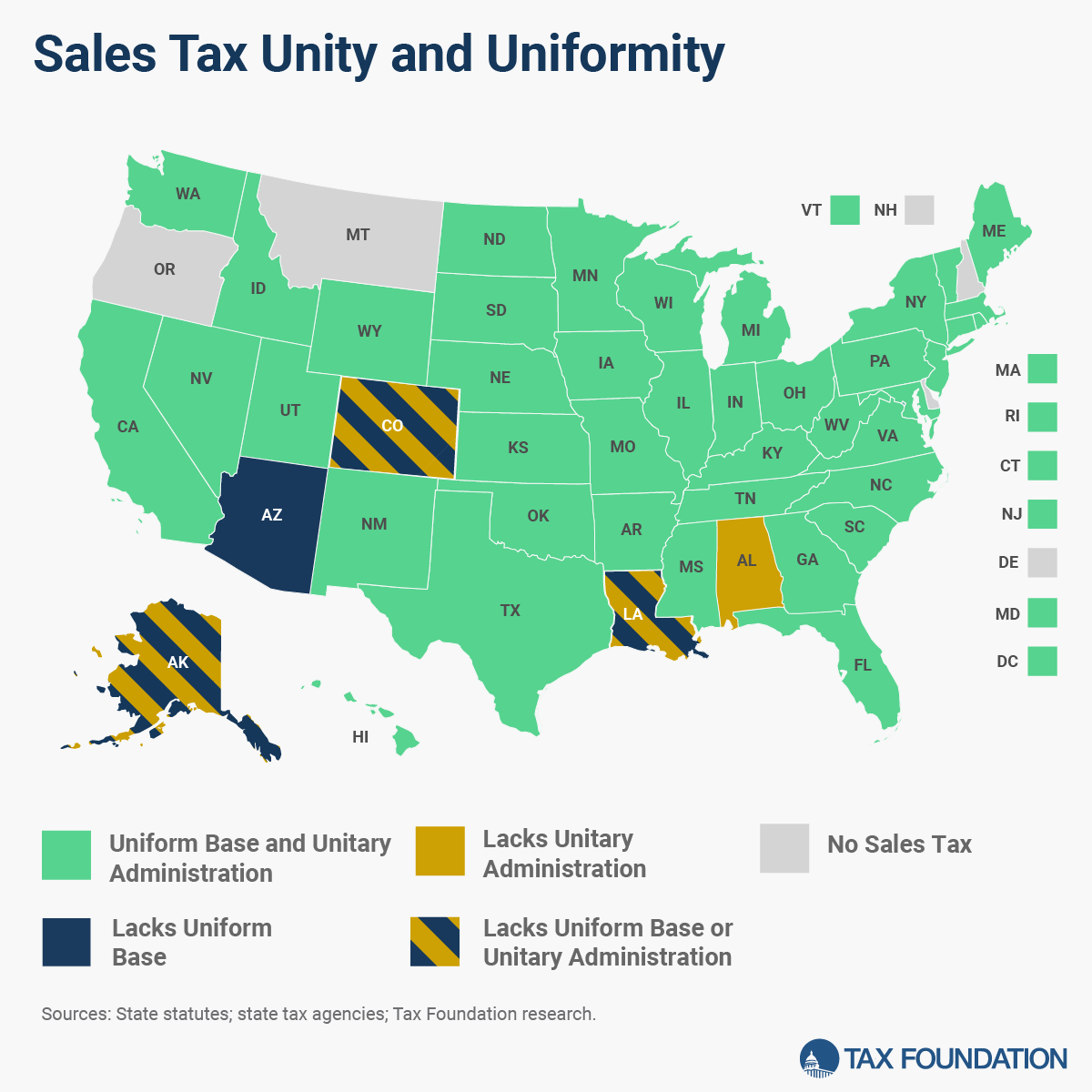

Four states—Alabama, Alaska, Colorado, and Louisiana—permit local sales tax administration.[49] In Alaska, this is an outgrowth of the state’s decision to forgo its own sales tax but to grant the authority to localities; in the other three states, it stems from strong home rule traditions and constitutional grants of local taxing power. Alabama has a uniform tax base, meaning that localities cannot make their own choices about what to tax and what to exempt, but many local governments handle their own tax administration, which would obligate remote sellers to remit separately to each jurisdiction. Arizona, by contrast, has centralized collections (a relatively recent development) but not full base uniformity. And whereas Arizona’s divergences are modest, Alaska, Colorado, and Louisiana allow broadly divergent tax bases, where different jurisdictions tax different baskets of goods and services. What is taxed in one jurisdiction may be exempt in another.

This lack of unity and uniformity has complicated efforts to tax remote sales at the local level, with Louisiana creating a special set of statewide rules for remote sellers and Colorado using a carrot-and-stick approach to nudge local governments into compliance. Alaska jurisdictions, meanwhile, have banded together to create a centralized point of administration for remote sellers. None of these solutions are perfect, and where there are gaps, many remote sales go untaxed—though the reforms represent significant progress.

Occasionally, as local option sales taxes are considered in states that do not yet authorize them, policymakers consider local administration. Very few policymakers in the handful of states that struggle under these systems would ever recommend them to others, and indeed have spent years—sometimes decades—attempting to unwind these patchwork systems, which yield low compliance and extraordinary administrative and compliance costs.

Establishing Sourcing Rules for Services

Under most circumstances, state sales taxes are destination-sourced, meaning that the relevant taxing authority is the one with jurisdiction over the location at which a customer receives a product. For these purposes, receipt is typically synonymous with taking possession, so a consumer who purchases an item in Philadelphia pays Pennsylvania and Philadelphia sales tax, even if she then takes her purchase home to New York City. If, however, she bought the product online and it was shipped to her New York City address, it is the New York state and local sales tax that applies.

For tangible property, sourcing is relatively easy. There tends to be a clearly defined physical location where a good is received. The same goes for some services, particularly those involving on-site labor. In many cases, however, services are performed in a different location than the one in which they are received. Hiring a home cleaning service poses few challenges—but how about a cloud computing service?

Sometimes the determination is complex. If a customer who lives in Chicago pays for a digital service offered by a company headquartered in San Francisco but served out of a data center in Phoenix, and that customer uses the service while on vacation in Honolulu, to which jurisdiction is the service sourced? Or if, for the sake of argument, business-to-business services are taxed (even though they should not be), if a company based in New York City pays for a customer relations database that is used by salespeople across the country, including sales teams based in Denver and Colorado Springs, is any portion of that transaction taxable in Colorado?

Within corporate taxation, some states have adopted a “look-through” approach for corporate apportionmentApportionment is the determination of the percentage of a business’ profits subject to a given jurisdiction’s corporate income or other business taxes. U.S. states apportion business profits based on some combination of the percentage of company property, payroll, and sales located within their borders.