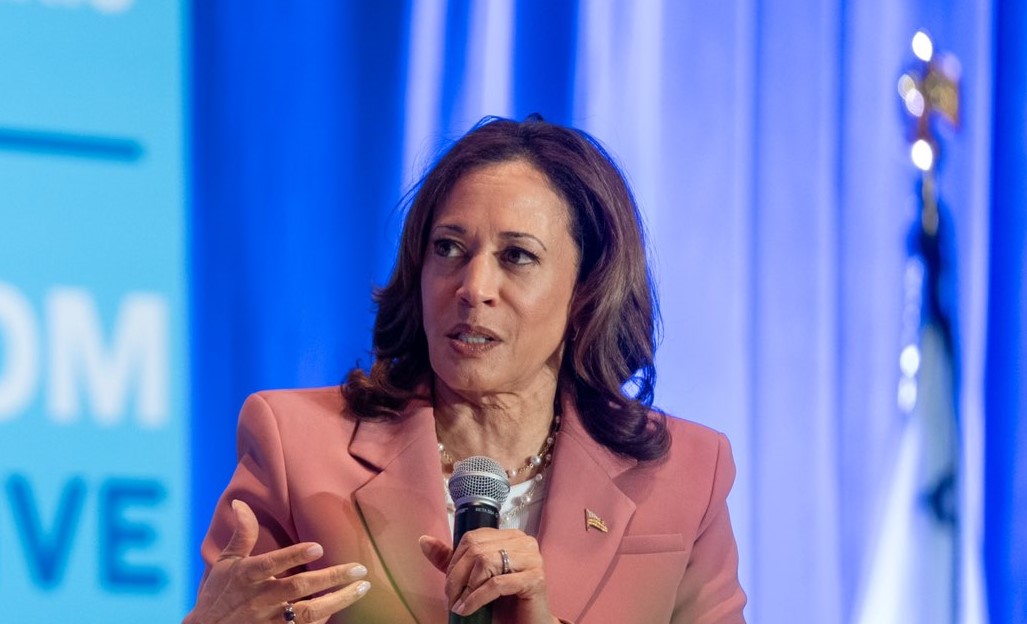

In her campaign for president, Vice President Kamala Harris has embraced all the taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities.

increases President Biden proposed in the White House fiscal year 2025 budget—including a new idea that would require taxpayers with net wealth above $100 million to pay a minimum tax on their unrealized capital gains from assets such as stocks, bonds, or privately held companies.

The so-called billionaire minimum tax would take the tax code in the wrong direction by imposing a complicated tax on a narrow segment of high-earning taxpayers in a way that’s never been tried. This proposal would add new compliance burdens for taxpayers and administrative challenges for the IRS while weakening the US economy by raising the tax burden on saving and entrepreneurship. It would also require a new wealth reporting system, allowing the IRS to track the wealth of an unspecified number of Americans every year (some people with less than $100 million of wealth would be required to report it to the IRS).

Under current law, taxpayers pay taxes on the growth in the value of their assets when they are sold (or realized). Gains on assets held for less than one year are subject to ordinary income tax rates, while gains on assets held for longer than one year are taxed at a top rate of 23.8 percent. Additionally, inherited assets receive a “step-up” in tax basis, eliminating tax owed on capital gains.

Under the new proposal, taxpayers with net wealth above $100 million would be required to pay a minimum effective tax rate of 25 percent on an expanded measure of income that includes their unrealized capital gains. Taxpayers would calculate their effective tax rate for the minimum tax and, if it fell below 25 percent, would owe additional taxes to bring their effective rate to 25 percent. Any additional taxes owed because of the minimum tax would be payable over nine years initially, and over five years going forward.

The change means wealthy taxpayers would owe taxes on capital gains each year, even if the underlying asset had not been sold. Any amounts paid would be treated as prepayments of future capital gains tax liability. For example, consider a taxpayer with net wealth of $200 million, $5 million in ordinary income, $10 million in accumulated unrealized capital gains from a privately held company, and an ordinary tax liability of $1.8 million (see accompanying table). When including unrealized capital gains as income, the household’s effective tax rate is 12 percent, below the proposed 25 percent minimum.

To increase their effective tax rate to 25 percent, the household would owe an additional $1.95 million in tax (resulting in a combined $3.75 million in taxes owed on $15 million of income when including unrealized gains). The $1.95 million could be paid in equal installments over nine years (for capital gains moving forward, minimum tax liability can be split into five annual installments) and would be credited against future capital gains taxA capital gains tax is levied on the profit made from selling an asset and is often in addition to corporate income taxes, frequently resulting in double taxation. These taxes create a bias against saving, leading to a lower level of national income by encouraging present consumption over investment.

liability on the asset when sold.

When the taxpayer eventually sells the company, the taxpayer would square up their taxes by using the prepaid taxes to offset capital gains tax liability. For example, if the household sold the private company in the future and owed $2 million in capital gains taxes, the taxpayer would reduce their liability by the $1.95 million prepayment and only owe an additional $500,000.

If the asset declined in value in a future year before being sold, it would produce an unrealized capital loss, reducing the taxpayer’s tax liability. An unrealized loss would first reduce remaining installments of tax owed on previous unrealized gains before being refunded in cash.

Overall, the proposal moves in the opposite direction of sound tax policy.

Changing the definition of taxable income to include unrealized capital gains presents significant administrative challenges, including how to value non-tradable assets and how to treat illiquid taxpayers who may have paper gains but lack cash on hand to pay their minimum tax bill.

The proposal attempts to meet such challenges with an entirely separate tax regime involving a deferral charge instead of prepayments for non-tradable assets and by allowing payment periods of nine years and five years. All options, however, introduce new complexities, opportunities for tax planning, and the potential of disputes with the IRS—in other words, economically wasteful activities. Additionally, the tax is levied on assets net of debts, meaning it could encourage additional borrowing to avoid the tax, unless mitigating rules are added.

The proposal would increase the tax burden on US savers, placing foreign savers at a relative advantage as they would not face the minimum tax. Raising taxes on domestic savers reduces the amount of domestic saving in the economy. In turn, foreign savers would finance a greater share of investment opportunities in the US. Over the long run, American incomes would fall as investment returns flowed to foreign savers instead of American savers. It would also manifest in a shifted balance of trade, increasing the trade deficit, all else held equal.

A higher effective tax rate on capital gains could also discourage angel investing, entrepreneurship, and risk-taking, reducing financing options for start-ups and leading to less economic dynamism.

The proposal runs contrary to international norms, as most countries in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development tax capital gains when they are realized, and at lower rates than the US, and tax capital income overall at lower average tax rates.

Another challenge is the minimum tax would likely be an unstable source of revenue. Much of the estimated revenue it would raise in the first decade is from taxing previously accumulated capital gains. Once taxes on the past accumulation of capital gains are paid, the permanent increase in revenue going forward would be smaller. Furthermore, because the revenue would depend on how taxpayers’ assets perform on paper, volatility in the stock market and the broader economy would translate into volatile revenue collections.

Harris’s billionaire minimum tax proposal would be a highly complicated new tax regime, creating new compliance costs for taxpayers and difficult administrative challenges for an already overwhelmed IRS without serving as a stable source of permanent funding. In addition, the economic harm could be substantial, as it would reduce saving, entrepreneurship, and economic dynamism. If lawmakers are seeking to raise revenue from top earners, they have much better options, such as progressive consumption taxes.

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

Share