Note: The following is the testimony of Daniel Bunn, President & CEO of TaxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities.

Foundation, before the U.S. Senate Committee on Budget hearing on April 10, 2024, titled, “Sunny Places for Shady People: Offshore Tax Evasion by the Wealthy and Corporations”

Chairman Whitehouse, Ranking Member Grassley, and distinguished members of the Senate Budget Committee, thank you for the opportunity to testify on offshore tax evasion.

At the outset, I want to distinguish between the concept of tax evasion, which is illegal and should be prosecuted, and tax avoidance, which is the utilization of legal methods to limit exposure to tax liability. Too often these concepts are conflated, and lawmakers and policy experts should be careful to identify the difference.

My view on evasion is simple: the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) should enforce existing tax rules so that criminal evaders of tax liability are brought to justice.

Avoidance is more complicated than evasion because it implies that the rules, as designed, allow businesses or individuals to legally reduce their tax burdens. This makes defining tax avoidance very difficult. Is it tax avoidance to utilize all available credits and deductions to arrive at one’s legal tax liability? Does tax avoidance become more salient if legal cross-border arrangements are being used by businesses or individuals?

Just as there are completely legitimate reasons for taxpayers to utilize credits and deductions, there are many legitimate reasons for individuals and businesses to earn income abroad.

In either case, policymakers may be concerned about the underlying tax rules. Some members of this committee may find it desirable to have a low tax burden on corporate or individual income, but the rules for such a system should transparently deliver that result. Instead, we often have rules that allow individuals or companies to achieve low tax burdens through complicated and less transparent maneuvers.

Other members of this committee may find it desirable to have a high tax burden on corporate or individual income. However, a higher tax burden also requires more substantial enforcement. In my view, the enforcement mechanisms aimed at offshore income are not too different from capital controls. Even with those enforcement mechanisms, the savviest companies and individuals may still be able to find gaps in the system resulting in a higher tax burden on those with less resources to explore and exploit enforcement gaps.

Policymakers should aim to align U.S. tax rules to support growth and investment while raising revenue with rules that are enforceable with low burdens for administration and compliance. Our current tax system does not measure up to those objectives. Specifically, worldwide taxation of individual income makes the U.S. a significant international outlier, and the worldwide Corporate Alternate Minimum Tax adopted in 2022 frustrates taxpayers and lacks final guidance from the IRS.

My testimony will cover official estimates of the tax gapThe tax gap is the difference between taxes legally owed and taxes collected. The gross tax gap in the U.S. accounts for at least 1 billion in lost revenue each year, according to the latest estimate by the IRS (2011 to 2013), suggesting a voluntary taxpayer compliance rate of 83.6 percent. The net tax gap is calculated by subtracting late tax collections from the gross tax gap: from 2011 to 2013, the average net gap was around 1 billion.

, the policy context for offshore income, and related issues for policymakers to consider with three key takeaways:

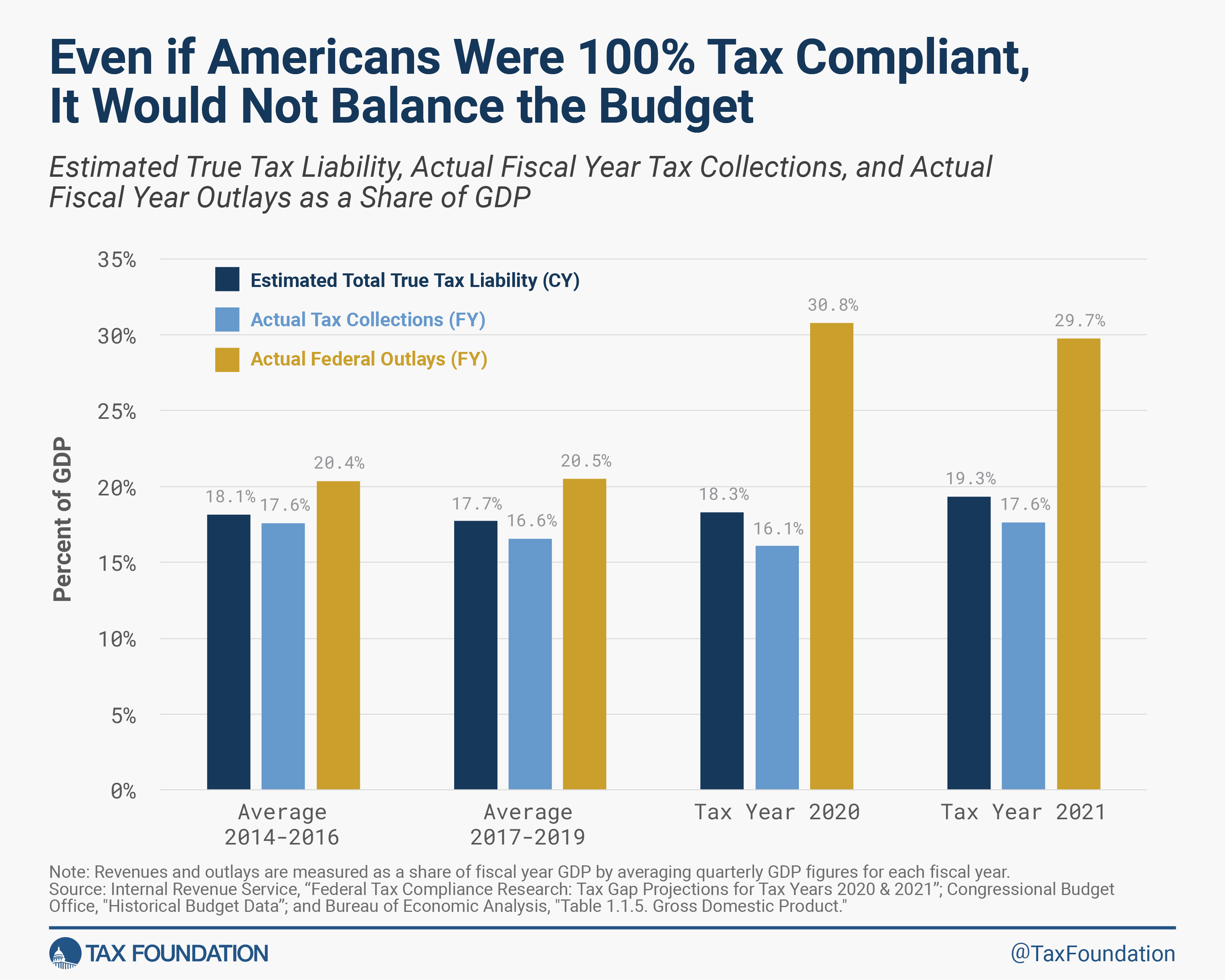

- The tax gap has remained roughly constant as a share of GDP and even full compliance would not close the deficit.

- Our citizenship-based income tax code creates headaches for taxpayers for not much revenue.

- The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) improved our international tax code by halting inversions and bringing back some profitable assets from offshore locations.

The Tax Gap

The most recent IRS report on the tax gap measured a projected tax gap of $688 billion for fiscal year 2021. On net, after accounting for enforced and late payments, the IRS projected a tax gap of $625 billion.[1]

This estimate does not indicate that $625 billion went unlawfully unpaid in 2021. The IRS instead uses estimates from prior analysis of tax compliance to estimate what is left unpaid.

The tax gap is impacted by taxpayer noncompliance, tax enforcement, and tax policy itself. This means that policymakers should think of the tax gap in terms of what can be done through policy to address the overall issue.

The size of the estimated tax gap has hovered around 2.5 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) in estimates the IRS has published over the last decade.[2]

The size of the tax gap is often pointed to as a way to solve the United States’ fiscal challenges. As my colleague, Scott Hodge, has written in his review of the IRS tax gap estimates, “…even perfect tax compliance—an impossible goal—would fall short of eliminating the deficit.”

Policies Impacting Offshore Income

The IRS notes in the tax gap report that their projections are limited and may not fully account for foreign income. Even without an official estimate of the tax gap for foreign income, it is worth reviewing the status of U.S. policies and their approaches to taxing foreign income.

The United States has historically been an outlier in its approach to taxing foreign income of U.S. citizens and U.S.-headquartered companies. The U.S. and Eritrea are the only two countries in the world that tax their citizen’s income no matter where they live. And until 2017, the U.S. was among only a handful of countries that did not provide a deduction or exemption for foreign business income. Alongside that change in 2017, the U.S. continues to tax the worldwide earnings of U.S. companies using several different rules.

Policies Regarding Foreign Individual Income

The challenges of enforcing citizenship-based taxation of individual income led lawmakers to adopt the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act (FATCA) in 2010. This law imposes a heavy compliance burden for banks around the world and U.S. citizens with earnings and savings abroad.

When the law was adopted, the Joint Committee on Taxation estimated that FATCA would raise $8.7 billion.[3] A 2022 report by the Treasury Inspector General for Tax Administration identified $574 million in costs of the first ten years of FATCA implementation.[4]

A 2019 report from the Government Accountability Office identifies other costs and challenges to FATCA.[5] Annual renunciations of U.S. citizenship rose from 1,601 to 4,449 from 2011 through 2016. The report notes that this increase of nearly 178 percent is “attributable in part to the [FATCA] difficulties.”

Many U.S. expatriates find themselves caught by the FATCA rules and overlapping compliance burdens. So-called accidental Americans, who may not even have been aware they were technically U.S. citizens prior to a FATCA compliance notice, have little recourse other than to formally renounce their citizenship.

Citizenship-based taxation is poor tax policy. And the FATCA, as an enforcement tool of that regime, has revealed the perverse incentives of enforcing such a policy.

Policies Regarding Foreign Business Income

Similarly, for business income, the policy landscape reveals the complexity that can arise in the context of a hybrid territorial tax systemA territorial tax system for corporations, as opposed to a worldwide tax system, excludes profits multinational companies earn in foreign countries from their domestic tax base. As part of the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), the United States shifted from worldwide taxation towards territorial taxation.

. In 2017, the U.S. adopted a deduction for foreign dividends as a transition away from a fully worldwide tax systemA worldwide tax system for corporations, as opposed to a territorial tax system, includes foreign-earned income in the domestic tax base. As part of the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), the United States shifted from worldwide taxation towards territorial taxation.

with deferral.

Prior to the TCJA, the U.S. operated a worldwide tax system with the option to defer taxes on foreign income until the earnings were repatriated, an approach most developed countries had abandoned in favor of a territorial tax system that largely exempts foreign earnings from domestic tax. To make matters worse, when U.S. companies brought earnings back, they faced a federal tax rate of 35 percent, which was the highest corporate tax rate in the Organisation for Co-operation and Development (OECD).

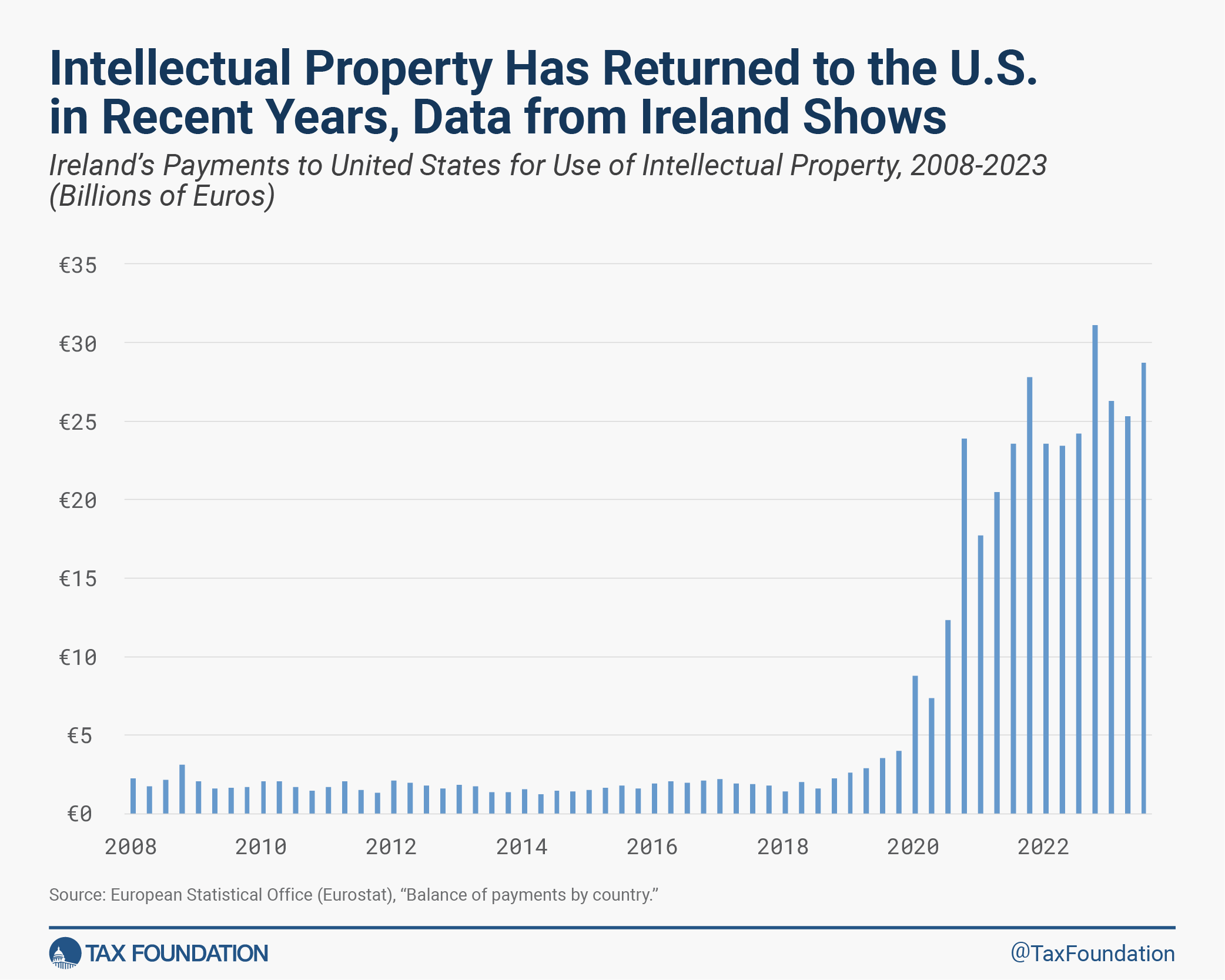

This incentivized U.S.-based business to either keep their earnings offshore or to move their headquarters to a foreign jurisdiction. Since 2017, trillions of foreign earnings have been repatriated, and tax inversions have stopped.[6]

Additionally, profitable business assets (namely, intellectual property assets) have been returned to the U.S. from offshore locations, as can be seen in recent data from Irish cross-border payments. Previously, payments from Ireland for using intellectual property owned by U.S. companies would flow to small offshore jurisdictions with no corporate income taxA corporate income tax (CIT) is levied by federal and state governments on business profits. Many companies are not subject to the CIT because they are taxed as pass-through businesses, with income reportable under the individual income tax.

. Following recent policy changes in the U.S. and Ireland, some of that intellectual property returned to the United States, and payments are flowing from Ireland to the U.S. because of that change.

U.S. business taxpayers must navigate a web of anti-avoidance rules, including our Subpart F regime, our tax on Global Intangible Low-Tax Income (GILTI), the Base Erosion and Anti-abuse Tax (BEAT), and the Corporate Alternative Minimum Tax (CAMT) adopted in 2022 as part of the InflationInflation is when the general price of goods and services increases across the economy, reducing the purchasing power of a currency and the value of certain assets. The same paycheck covers less goods, services, and bills. It is sometimes referred to as a “hidden tax,” as it leaves taxpayers less well-off due to higher costs and “bracket creep,” while increasing the government’s spending power.

Reduction Act. Each of these come with their own complexities and challenges, but the CAMT stands out as taxpayers still do not have final guidance from the IRS for complying with that policy.

Likewise, the global minimum tax will introduce a new level of complexity for U.S. multinational businesses, even if the U.S. does not adopt those rules.

Meanwhile, measures of profits of U.S. companies in tax havens show that the overall amounts of profits in those jurisdictions is relatively small. Some measures show a decline in recent years. As Adam Michel of the Cato Institute pointed out in a recent report, since 2016, the haven profit share of direct investment income has been declining.[7]

This supports the idea that the rules adopted in 2017 improved the tax treatment of foreign earnings, made the U.S. a more competitive location for earning profits, and that lawmakers should be careful not to upset this balance.

Conclusion

Policymakers should aim for policies that are pro-growth, efficient at raising revenue, and enforceable. Our current rules for foreign income fall short, particularly our citizenship-based taxation of individual income and the Corporate Alternative Minimum Tax.

Over the last decade, there has not been a meaningful change to the tax gap. Policymakers should focus on specific rules they want to change to limit avoidance or enforcement measure they think will address evasion.

U.S. policymakers will likely be considering changes to rules for offshore income as part of legislation to address the expiring Tax Cuts and Jobs Act provisions in 2025. In that context, lawmakers should aim for policies that support investment and hiring in the United States and refining anti-avoidance measures to improve administrability and lower compliance costs.

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

[1] Internal Revenue Service, “Federal Tax Compliance Research: Tax Gap Projections for Tax Years 2020 & 2021,” Oct. 2023, https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-pdf/p5869.pdf.

[2] Tax Foundation, “IRS Report Shows Closing the Tax Gap Would Not Close the Deficit,” Oct. 25, 2023, https://taxfoundation.org/blog/irs-tax-gap-report/.

[3] The Joint Committee on Taxation, “Estimated Revenue Effects Of The Revenue Provisions Contained In An Amendment To The Senate Amendment To The House Amendment To The Senate Amendment To H.R. 2847, The ‘Hiring Incentives To Restore Employment Act’ Scheduled For Consideration By The House Of Representatives,” March 4, 2010, https://www.jct.gov/publications/2010/jcx-6-10/.

[4] Treasury Inspector General for Tax Administration, “Additional Actions Are Needed to Address Non-Filing and Non-Reporting Compliance Under the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act,” Apr. 7, 2022, https://www.oversight.gov/sites/default/files/oig-reports/TIGTA/202230019fr.pdf.

[5] U.S. Government Accountability Office, “Foreign Asset Reporting: Actions Needed to Enhance Compliance Efforts, Eliminate Overlapping Requirements, and Mitigate Burdens on U.S. Persons Abroad,” Apr. 1, 2019, https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-19-180.

[6] For more information on the 2017 rule changes and their impact, see Alan Cole, “The Impact of GILTI, FDII, and BEAT,” Jan. 31, 2024, https://taxfoundation.org/research/all/federal/impact-gilti-fdii-beat/.

[7] See Figure 4 in Adam N. Michel, “Bold International Tax Reforms to Counteract the OECD Global Tax,” Feb. 13, 2024, https://www.cato.org/policy-analysis/bold-international-tax-reforms-counteract-oecd-global-tax#data-multinational-business-income-overstates-tax-haven-profits.

Share